“In the history of civilization, there likely hasn’t been anything that has caused more conflict than either land (and who controls it) or religion. And part of that is because these are two of the most powerful leverage points for change in a civilization.”

That’s what Molly Burhans, the founder and executive director of a nonprofit called GoodLands, incisively pointed out during a recent interview. And she would know: her organization, with help and support from Esri, is currently mapping out all the land owned by the Catholic Church.

“The way we use our lands has a moral dimension,” said Burhans, who was exploring becoming a nun in college when she first noticed that the Church was unwittingly overlooking its most financially and politically powerful asset—its land. “The environment is the spatiotemporal matrix where all our good works play out. You can be a person who cares about the earth, and you can ignore the poor and ignore all the vulnerability in society. But if you’re a person who cares about the poor and the sick, you can’t ignore the environment.”

The way landscapes are constructed has a profound influence on everything, she remarked, from child development and asthma to education and economic status.

“The environment is critical for almost every mission of the Church,” Burhans added. “How we use our land can change the world. But we need maps to make smart decisions about it.”

While nobody really knows how much land the Church owns, it is certainly one of the largest private landholders in the world. Considering that it runs the most extensive network of health-care institutions and nongovernmental schools around the globe, it would be no surprise, according to Burhans, if the Catholic Church did control the largest amount of land on earth.

But the last maps the Catholic Church made of its landholdings date back to the Holy Roman Empire. Burhans and her team at GoodLands—which now consists of herself, 14 part-time employees and volunteers, and a network of about 50 technology contractors—essentially had to start from scratch. The data that is needed to create a high-level map of the Church’s georeligious boundaries is scattered all over the world—from libraries in Connecticut to streetside posters in Hyderabad, India. But because Burhans possesses an exceptional capacity to think about the big picture while not letting any of the details slide, this truly monumental project is making progress, producing the most expansive yet comprehensive map and dataset of Catholic-owned land the world has ever seen.

Seeing the Whole but Not Overlooking the Parts

It seems that Burhans has always been able to consider broad strokes and minutiae concurrently. The daughter of two scientists, she started dabbling in scientific illustration when she was 14 years old. At first, she just did it for them. But then their colleagues began reaching out to her with projects, so she made illustrations in exchange for their lecture notes and syllabi.

“When I was younger, I was so interested in how the human body worked, but it seemed so complex,” she recalled. “I drew on this big sheet of paper this massive, empty human body, and I used layers of tracing paper to fill it in with all its parts.”

Using intricate layers to fill in a blank slate and distilling complex ideas into a visual display, Burhans unsurprisingly sees a direct correlation between scientific illustration and cartography.

“If you’re putting an illustration together of a human ear, that’s just like the layers of a map,” she said. “My brain was already in this space to be thinking just like GIS when I encountered it.”

But that didn’t happen until she went to graduate school. First, she took a few years after high school to travel and work with nongovernmental organizations before attending Canisius College in Buffalo, New York, where she majored in philosophy. While there, Burhans cofounded her first company, GroOperative, an indoor vertical farm that grows food in stacked layers and turns all its profits over to farmworkers. This is also when she spent time at a Catholic congregation in the northeastern United States, getting to know the ways of its nuns. It was here that she observed the Church’s shortcomings in land management.

“I saw that these sisters were some of the most holy, good people in action. I mean, they were getting rival gang members to bake bread together. But they had a lot of houses in the inner city that were underused, and their mother house in the country had unkempt swaths of forest and acres of mown lawns,” Burhans recalled. “I thought I should help them figure this out before seriously considering joining any specific religious community. Along the way, I discovered that no one was really helping the Church manage its real estate in a way that’s aligned with its mission.”

With this in mind, Burhans entered a graduate program in ecological design at the Conway School, a unique program in Northampton, Massachusetts, that emphasizes teaching whole-systems theories for sustainable landscape planning and design. That’s where Burhans first encountered Harvard Graduate School of Design professor emeritus Carl Steinitz’s work and was able to apply the concepts of geodesign to the real world via the client projects she and her classmates had to do.

“I had this really amazing, very flexible education that allowed me to explore and live the geodesign methods in practice,” said Burhans.

While the majority of students who graduate from Conway go on to found their own landscape companies, Burhans took a bit of a different approach to her entrepreneurial aspirations. She decided that geodesign was the way she could parlay her landscape design-based education and interest in cartography into a venture that could help Catholic dioceses—and those nuns she so greatly admired—more sustainably manage their land and real estate holdings.

“I took less than a week off between finishing grad school and founding GoodLands,” she said.

From One-Off Projects to a Worldwide, Cloud-Based System

Once Burhans set up GoodLands, she wanted to do a complete land analysis before getting any contracted jobs. Working out of the Hartford Public Library in Connecticut, she used the Hartford Archdiocese as a prototype.

“I wanted to work through what a project would look like and then pitch it to them,” she said. “I started to just map out all the information within the archdiocese that I could find.”

She used a lot of data from the University of Connecticut, the state, and local municipalities to see what was there and then did an environmental analysis of everything the archdiocese owned. Burhans quickly learned that her organization needed to offer broad solutions that encompass three key domains: the environment, financial concerns, and social issues.

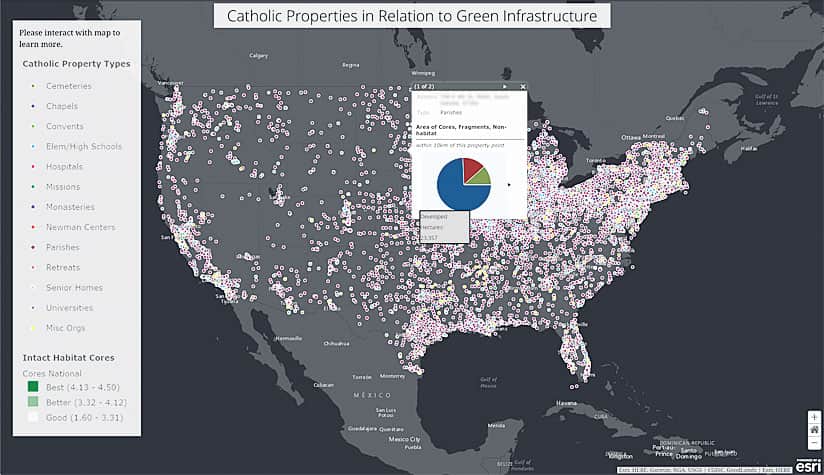

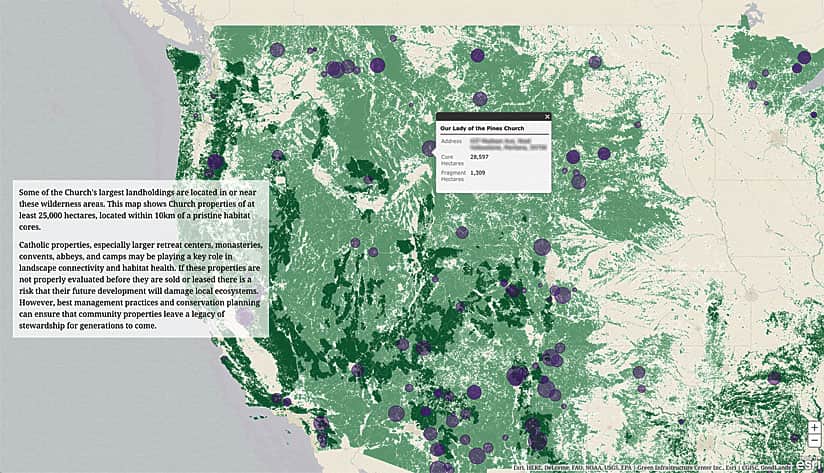

This project also gave Burhans an inkling of what Catholic land looked like around the world, so she started thinking bigger than doing one-off projects for individual dioceses. What if she could build a global database of all the land the Catholic Church owned to help members and leaders of this major world religion understand the environmental value of their property and how it relates to space? She could not only educate dioceses on how to conserve portions of their land to protect threatened species, but she could also formulate a comprehensive overview of how the Church can use its land to help tackle huge problems such as climate change and mass migration.

I don’t want to give people a master plan that sits on a shelf. I want to give people their maps, their entire plans, in a cloud-based format that they’ll use.

With this outlook, the fledgling organization grew in importance fast. Not even a week after launching the GoodLands website, Landscape Architecture Magazine reached out to Burhans to do a story on her and her project. That was the first piece of press ever about GoodLands, and after its release in December 2015, the momentum kept building. Pope Francis had released his encyclical on the environment, Laudato si’, earlier that same year, which prompted the formation of a global community to figure out how the Church relates to sustainable development and environmental challenges. Additionally, the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP 21, took place in Paris around the same time the Landscape Architecture article came out.

“The timing was perfect,” recalled Burhans. “I just felt it. The fact that we are faced with this massive, daunting challenge not only of our environment being destroyed around us…but also of migration inevitably increasing in the coming decades, I knew that a project like GoodLands needed to happen.”

The following month, Burhans and two of her mentors flew out to Redlands, California, to give an executive briefing to Esri president Jack Dangermond and his advisory team about mapping the Catholic Church’s boundaries worldwide.

“We got a small grant from Esri, and then [Dangermond] opened up the Esri Prototype Lab to GoodLands, which was invaluable,” said Burhans.

She spent time at Esri as a visiting researcher, working with the Prototype Lab to create a dynamic map of all the land the Catholic Church oversees. Burhans also worked with Esri Professional Services to start designing a spatial data infrastructure (SDI) for the Catholic community. And the cartography team helped her make web maps for a map exhibit in the Vatican’s Casina Pio IV villa as part of the Vatican Art and Technology Council.

Around the same time, Burhans visited Vatican City and met with the Secretary of State’s office to see if she could obtain any global boundary datasets the Holy See had for Catholic parishes, dioceses, and conferences around the world. There were none.

“They hadn’t had a map update since the Holy Roman Empire,” recalled Burhans. “I asked, ‘Is there any reason why this hasn’t happened, and do you mind if I do this?’ They looked at my prototypes and said that, yes, global boundary sets would be useful.”

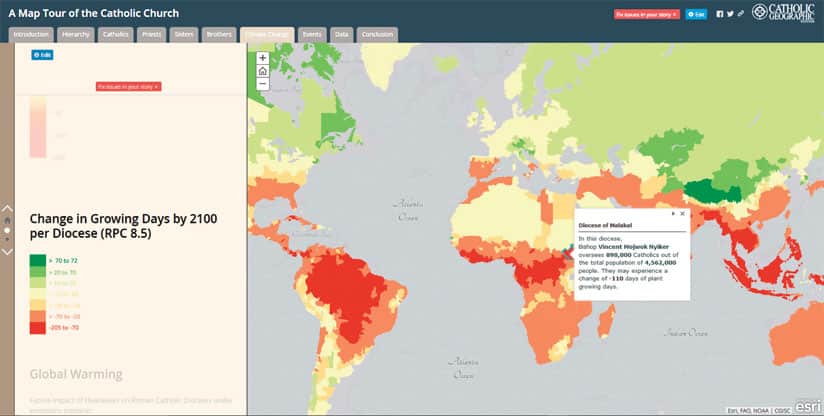

With tacit approval from the Vatican to continue with the project, Burhans set about expanding GoodLands’ offerings. The organization does a range of specialized projects for individual dioceses and other landowners: coming up with holistic master plans for how to best use land and real estate, doing climate change risk assessments, developing map-based communication systems, and building GIS-based data structures. It is also weaving this into a larger network of spatial data that Burhans hopes can bring the Catholic Church’s maps into the twenty-first century.

“A lot of the Church is still pre-digital transformation by hundreds of years,” said Burhans. “I am so excited about the possibility of getting the entire Church into the digital age because I think it has a really important role in multiple ways—one of them being understanding a healthy relationship with technology and another being how we can ensure the intelligent and respectful use of data,” which could be akin to formulating a sort of digital canon law.

The map of the boundaries of Catholic-owned lands is the basis of all GoodLands’ work, but there are hundreds of maps buttressing that. GoodLands has close to 1,000 maps in its back end, both on- and offline, that stem from various projects, including client work and activities with the Vatican. And Burhans and her team employ a range of ArcGIS technology to execute their groundbreaking mission—from ArcMap, ArcGIS Pro, and ArcGIS Enterprise for doing heavy mapping and data management to Survey123 for ArcGIS for data collection, Esri CityEngine for 3D modeling, and GeoPlanner for ArcGIS for planning and design. Burhans hopes to soon incorporate ArcGIS Hub into the stack to help individual dioceses manage and share their data on their own.

“I don’t want to give people a master plan that sits on a shelf,” explained Burhans. “I want to give people their maps, their entire plans, in a cloud-based format that they’ll use.”

And that’s exactly what a robust GIS can do.

Stewarding This Invaluable, Groundbreaking Data

Burhans has met Pope Francis three times since founding GoodLands. Once, she presented him with a version of the master boundary map, which he received with a lively smile. When she met the pope again this past summer, it set in motion a venture that Burhans never could have imagined.

“I received some permissions to establish a test-run cartography institute in the Vatican under the Pontifical Academy of Sciences,” said Burhans. “While we have initial approval, we are all deliberately moving slowly.”

Discussions are ongoing around how the institute could work to be most beneficial to the Church’s current needs, while Burhans and her team proceed with side projects and research that are relevant to the Vatican’s goals.

“This would be the first scientific institution founded in the Holy See since the Vatican Observatory,” Burhans pointed out.

It was that observatory that ushered in the Gregorian calendar, which much of the world uses today. And that calendar was approved by Pope Gregory XIII. So Burhans understands how consequential this new institute could be and how far papal approval can take something.

“GoodLands has the only global boundary dataset for the Church and a growing catalog of information about its property assets around the world,” said Burhans. “Because we have this, I’m hoping we can help establish the cartography institute’s structure and then let it go from GoodLands and have it become part of the Holy See. From the institute, in the long run, I feel like we could see the emergence of the authoritative boundaries of the Church.”

For now, however, the global boundaries are being mapped and released cautiously, so far only available via video demonstrations that don’t allow users to interact with the data. This is intentional. Burhans wouldn’t want to pinpoint where every Catholic Church is in environments that are hostile to Christianity and then have people get hurt because of that.

“This is the first time any major world religion has been mapped around georeligious boundaries,” she said. That carries with it a great responsibility, which Burhans is well suited to shoulder.

“I don’t know why I am the person who ended up in this position…but I’m really grateful that I have had this mind-set of looking at the big picture,” she reflected.

Burhans does expect that within the next 5 to 10 years, a public version of the boundaries will be released. But she’s looking toward the Vatican to steward that data. Then, who knows how far it could go in helping nonstate actors—the Church, businesses, and nongovernmental organizations—manage complex issues, from climate change and food security to migration and so much more.

For more information about GoodLands, email info@good-lands.org and explore the Making Land Work for Good and Map Tour of the Catholic Church story maps.