After Hurricane Maria roared through Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017, the island was in a state of total chaos. The category 4 storm destroyed the power grid, leaving all 3.4 million residents without electricity; decimated already-aged infrastructure, rendering many roads and bridges unusable; and devastated communication networks, cutting off Internet and cell service almost completely.

Disaster response and recovery efforts were going to be difficult. The unincorporated US territory, which declared bankruptcy that May, hadn’t even recuperated from Hurricane Irma, a category 5 storm that grazed the island two weeks prior and left 80,000 people without power.

Within days of Maria, a number of federal and state agencies descended on Puerto Rico to help out. These included the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA); the US Army Corps of Engineers; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); the US Department of Veterans Affairs; and scores of police officers, firefighters, and paramedics from New York, New Jersey, California, Arizona, and elsewhere. The Puerto Rico Planning Board was at the helm, with extensive support from the island’s department of transportation, police department, and cadastre unit, along with several private companies and nonprofit organizations.

Once everyone in Puerto Rico was able to get out of their houses and make sure their families were safe—which took a few days—the central government set up an Emergency Operations Center (COE in Spanish) at the convention center in the capital city of San Juan. From there, all these organizations began coordinating efforts to restore the power grid, fix roads and bridges, get medical aid and disaster relief to residents, and assess the damage. But with all forms of digital and mobile communication down, they were going to need to get creative.

When staff from Geographic Mapping Technologies, Corp. (GMT), got to the COE, they saw that the organizations were working pretty independently of one another. Many agencies had brought GIS teams, so they were making their own maps and printing a lot of them out to take into the field. Additionally, everyone seemed to have separate maps of key locations: cell towers, gas stations, hospitals, and supermarkets. That wasn’t going to get anything done quickly. So GMT, Esri’s official distributor in Puerto Rico, stepped in.

With assistance from Esri’s Disaster Response Program (DRP), staff from GMT not only integrated everyone’s GIS resources into one place, but they also built innovative apps that field crews could use to collect and share data—even offline. This made the response go much faster than it would have otherwise.

“And that’s so strange because, for us”—the residents of Puerto Rico—“it took forever,” said Glenda Román, GMT’s professional services manager.

Data All Over the Place

No one in Puerto Rico anticipated that the aftermath of Hurricane Maria would be as bad as it was.

“We didn’t expect to be with everything one day and then nothing the next day,” said Diego Llamas, the technical support manager for GMT. “Communications, the Internet, and all the facilities you have using your cell phone—those didn’t work.”

This was a huge problem for the organizations orchestrating the response.

“Their own apps worked in the field only if there was Internet or [a] mobile connection,” said Alberto Millán, a GIS analyst for GMT. “When they got to Puerto Rico, they had problems because there was no service.”

Scrambling to get their operations under way, the various GIS units started printing out maps—hundreds, maybe thousands of them. The GMT team noticed immediately that this was causing many agencies to duplicate efforts.

“Data was all over the place, and nobody was getting that data,” recalled Román.

GMT’s president, Aurelio (Tito) Castro, agreed with the planning board that everyone needed to start collaborating—quickly—and begin using the same dynamic data to get a robust response going.

The Puerto Rico Planning Board already had an ArcGIS Online account, so Castro interfaced with the DRP team—which reached out to him the day after the hurricane to offer GMT any help it needed—to get extra licenses and credits.

“The first thing we did was set up as a hub through the ArcGIS Online account for the Puerto Rico Planning Board,” said Román.

“Since that day, we started growing the users in the planning board’s system, [and everyone] started putting information into the common platform,” added Castro.

“We connected all these agencies through creating groups and sharing content,” continued Román. “By doing that, we were able to provide one space where all these first responders could gather local data [on] roads, hospitals, gas stations, supermarkets, [and] criminal incidents.”

They also started receiving a steady stream of documents and links from the DRP that contained data, images, and apps from people around the Esri community who were working to help Puerto Rico with the response.

“The [DRP] was very, very helpful in providing us with other data that we were not aware had been published by other groups, including services, aerial photographs, [and] information published by federal agencies,” said Castro.

To continue getting the GIS support it needed, GMT was in constant communication with the DRP in the days and weeks following the hurricane.

“We had many conversations via text in the middle of the night just to get things up and running,” said Brenda Martinez, the disaster response and public safety marketing specialist at Esri.

“It’s very important that people around the world understand that Esri has this capability 24/7,” said Castro. “I called these guys on Sundays, on Saturdays, at 9:00 p.m., at 1:00 a.m. They gave us the support.”

A Special Locator and a Customized App

After deploying ArcGIS Online as a hub, the next issue was getting these agencies and organizations off paper maps and onto mobile apps so they could coordinate more seamlessly.

“All these people needed to move in the field, and that’s why they were requesting paper maps,” recalled Román.

But even with paper maps, rescue and recovery workers were having a hard time finding the addresses they were looking for. That’s because addressing outside city centers in Puerto Rico is complicated.

“In urban areas, it would work just as in the US, with street names and numbers,” said Román. “But once you get…in the rural areas, you won’t have house numbers or even street names.”

Instead, the main thoroughfares are numbered state roads that have markers at each kilometer. From there, interior roads branch out like limbs on a tree.

“The closest you can get to a physical address is the kilometer. From that point onward, you have to use references and ask people how to get around,” explained Román. “That’s the biggest challenge that first responders faced—because how do you reach those areas if you don’t have an address?”

The lack of Internet and mobile connectivity made this worse. But GMT staff had a solution in mind; it would just take a bit of rigging.

Esri had already worked with GMT to improve geocoding so it was more compatible with the needs in Puerto Rico’s rural areas.

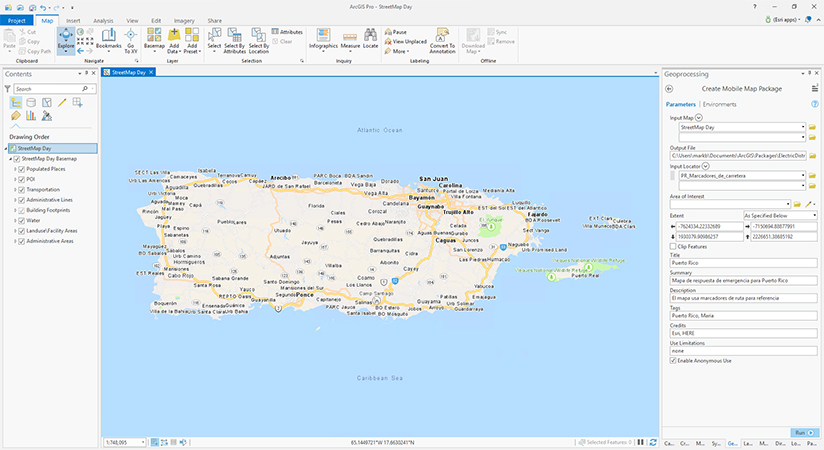

“We built a special locator for them where they could type in the distance—0.1 kilometers, 0.2 kilometers—along the road and find that location,” said Jeff Rogers, the geocoding program manager at Esri. “We’d built this capability for them into online services, and they’ve been using that for years. But when the Internet went down, we needed to pull together a local, offline solution.”

Several teams at Esri worked with GMT for about a week to build a custom search capability, along with a customized version of the Explorer for ArcGIS app, that would enable first responders to go out into rural areas with handheld devices to find and report on people who needed assistance and incidents that required attention—all without Internet or cell connectivity. This entailed building a composite locator based on all sorts of data from different agencies and using parcel data to build the geocoder by name.

“We didn’t have addresses, but we did have the names of who owns the land. So we geocoded the names,” explained Román. “Then, once you get to the kilometer, you can actually figure out how to move to [a] house by identifying the owner’s name.”

This proved indispensable to getting field crews out to their assignments so they could provide support and do inspections of damaged infrastructure and buildings.

“This was a good test for the disconnected functionality because there was actually no Internet, and it worked superbly,” added Román.

Different Agencies, Different Needs

GMT’s work didn’t stop there. The team built six custom apps in total and collaborated with all the organizations at the COE to get them the GIS services and apps they needed.

“With different agencies, we had different jobs,” recalled Llamas. “One of them asked for the geocoding. Other ones asked for surveys. Other ones wanted to collect information.”

In addition to Explorer, the team employed Survey123 for ArcGIS, Collector for ArcGIS, Web AppBuilder for ArcGIS, and Operations Dashboard for ArcGIS to help each agency and organization get its work done more efficiently.

This was a good test for the disconnected functionality because there was actually no Internet, and it worked superbly.

The US Army Corps of Engineers, for example, inspected a lot of infrastructure and provided direct aid to residents. Its team members employed the customized Explorer app heavily to figure out where to land helicopters in rural areas and determine how bad the damage was to houses and other structures.

The CDC benefited from having the four or five paper-based forms it was using entered into Survey123 so it could gather and disseminate health data digitally rather than running paper work back and forth across the island.

The GMT team also helped municipalities digitize their data collection efforts and workflows. Staff at the Caguas municipality, for example, wanted to track their progress with clearing roads of downed trees and garbage. They also wanted to update citizens on which roads and bridges were open for transit and which ones weren’t.

“We made dashboards and web maps for them, and they used ArcGIS Pro,” said Millán.

Once the team from GMT got going, most of the apps took just 10–45 minutes to build, while the more complicated ones required, at most, two or three days. Soon, about 90 percent of the organizations at the COE were using ArcGIS technology, according to Castro’s estimate.

“We had to do more with fewer resources, and the ArcGIS platform was crucial to that,” he reflected.

A Platform That Made the Difference

With all the agencies using GIS apps both in the field and back at the COE, local police sharing crime data almost constantly, the transportation agency updating people on road conditions every day, and everyone receiving additional data through the DRP—all in ArcGIS, and all without connectivity in the field—disaster response efforts picked up. But things still moved slowly.

“Typically, the response phase lasts a couple of days to a couple of weeks,” said Jeff Baranyi, Esri’s public safety assistance program operations manager. “For Puerto Rico, they were in response mode for several months. The whole country seemed to be relatively crippled. The magnitude of damage was quite vast.”

It took the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority 11 months to report complete power restoration. Washed out roads and bridges are still being repaired. And a study from George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health estimated that in the six months after Hurricane Maria struck, anywhere from 2,658 to 3,290 excess deaths occurred due to the extended relief and recovery process.

“The hurricane was way beyond any historic memory there is here in Puerto Rico,” said Román. “But using the ArcGIS platform was a way of bringing together all the agencies, of sharing data on Puerto Rico, [and] of helping organize the response efforts and then the recovery efforts. Everything could be easily deployed, and so fast—no programming needed. And I think that really made a difference. Without that, the response would have been slower than what it actually was.”