Annette Ginocchetti has boundless enthusiasm for GIS. She is also always one step ahead with the technology.

Ginocchetti helped build a 3D dataset of major US cities long before digital twins were a thing. She used GPS to map and classify roads all over the United States, which laid the groundwork for the ubiquitous mobile navigation systems of today. She advocated for open data well in advance of many organizations making it a priority. And she’s now implementing hub-based GIS solutions that integrate all sorts of technology—including payment systems—with GIS.

“GIS is a fantastic field, and it’s super special to be in it,” said Ginocchetti, the GIS services manager at the Northeastern Pennsylvania Alliance (NEPA), a nonprofit community and economic development agency. “I’m so proud and thankful and feel very blessed to be part of this world.”

A lover of the outdoors, Ginocchetti recognized early on that she wanted a career that got her out into nature.

“I was working for my family’s shoe store and knew I didn’t want to be in retail,” she said. “I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do in life, but I figured environmental science sounded good.”

That’s the major she chose as a sophomore at a Pennsylvania State University branch campus. Around the same time, a friend of her mom’s encouraged her to apply for an internship at the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. She got it.

“They handed me a GPS receiver and asked me to go out and locate all the abandoned landfills in northeastern Pennsylvania. I thought, what a great job this would be, working with satellites and working outside,” she said. “I fell in love with GPS and GIS technology.”

Ginocchetti soon transferred to the main Penn State campus, where her major fell under the College of Agricultural Sciences.

“[There were] a lot of farmers,” she said. “It just wasn’t what I thought it was going to be.”

She went to her guidance counselor and asked where all the GPS and GIS classes were.

“She asked, ‘Like space?’ And I was like, ‘I guess so.’ So she said to check out the College of Earth and Mineral Sciences,” Ginocchetti recalled. “When I went there, I discovered that that’s where all my people were!”

Ginocchetti dropped her environmental science classes and picked up a bunch of geography classes. She was told that she could study the history of geography and become a teacher or focus on digital geography.

“By default, I chose the latter, and I’ve never looked back,” she said. “It was one of the greatest decisions of my life.”

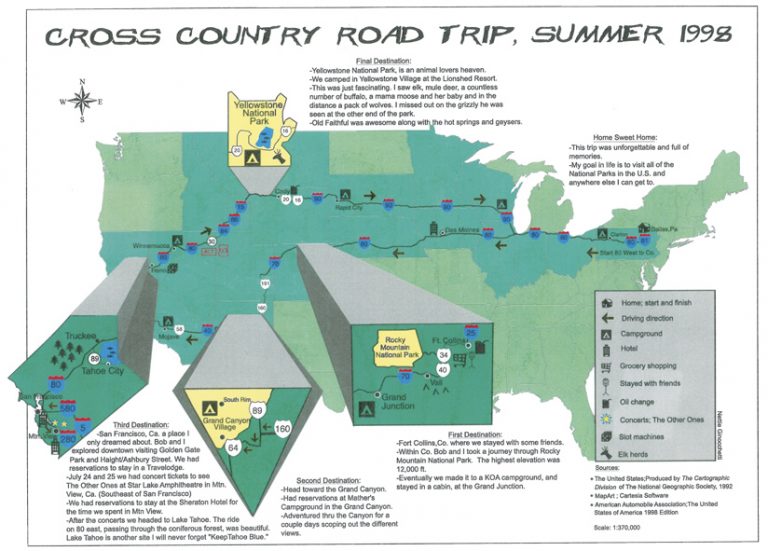

Despite not having much of a mapping background—she once drove through the Mojave Desert to attend a Grateful Dead concert and had difficulty figuring out where she was while using a paper map—Ginocchetti’s first professional ventures in the industry were foundational to modern mapping technology.

After college, she was hired as a GIS analyst for a mapping company called Urban Data Solutions. Her primary responsibility was to attach spatial attributes to photographs of buildings in major US cities. The company then pitched the 3D photos and datasets to gaming companies, real estate agencies, government organizations, and more.

“We built the first 3D dataset of all the major cities in the United States,” she said.

Soon, however, Ginocchetti noticed that her coworkers were being laid off, so she started sending out her résumé. Sure enough, Urban Data Solutions shut down.

Within a week, a digital mapping navigation company called Etak recruited Ginocchetti for a data collector position. While she was at a six-week training course on how to map and classify roads based on their function, Etak was bought out by Tele Atlas, whose parent organization is now Esri partner TomTom.

“At the time, Tele Atlas and NAVTEQ [now owned by Esri partner HERE] were two companies going head-to-head to map the United States for in-car navigation. So there was a rush to map the functional road classification in the United States,” Ginocchetti explained. “Tele Atlas sent me home with a company car, a pentop computer, and a dataset. I was responsible for mapping all the roads in northern New Jersey.”

Ginocchetti was told that one day she’d be able to stand on a street corner and see all the streets appear in a map on her cell phone. At the time, that seemed a little futuristic, she thought.

“I had no idea back then how big this was going to be,” she said. “But I loved my job. I loved being on the road. I loved mapping reality.”

She won awards for the quality of her data and even got to map rural areas in Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana. But she saw that Tele Atlas was starting to sell its cars and lay people off, so once again, Ginocchetti began circulating her résumé. This time, she wanted to work closer to home, ideally in Philadelphia. A GIS analyst opportunity arose at the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC), and she jumped at the chance to work there.

“When I interviewed for the job in Philly, I didn’t know how to explain to them what I did, so I streamed my drive to the interview,” she said. “I mapped the whole ride down, and they could see the GPS tracks—which I called Nettie’s Spaghetti—all the way to the parkade.”

Ginocchetti landed the job, which allowed her to bridge all the mobile work she’d been doing with her education in GIS. She made maps for the planning commission using ArcGIS 8.x—which was new technology for her—and credits her colleagues at DVRPC with teaching her a great deal about GIS.

From there, Ginocchetti moved even closer to home and got a management-level job at Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, as its shared GIS resource. While there, she advocated for open data and led projects that included making flood maps and doing 911 readdressing.

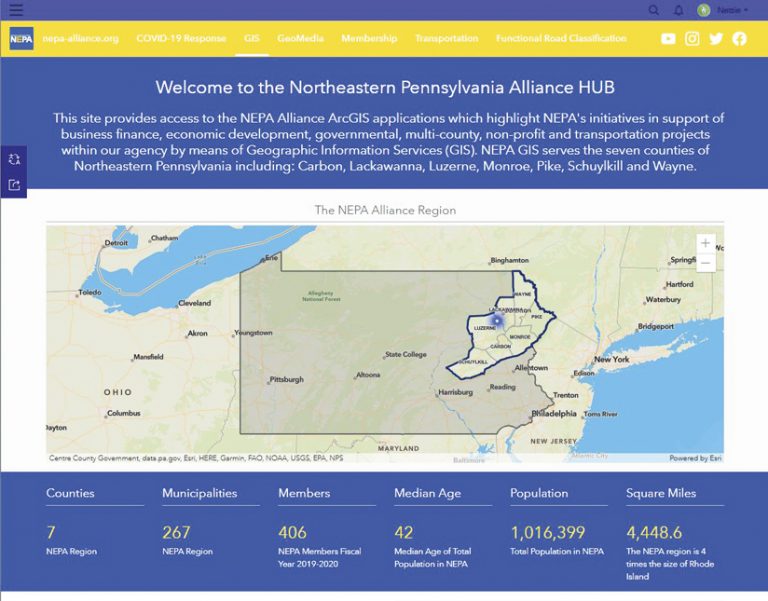

After seven years, Ginocchetti’s increasingly comprehensive experience made her a shoo-in for a GIS transportation specialist role at NEPA, the position she held before being promoted to GIS services manager. The alliance represents seven counties in northeastern Pennsylvania, and that has allowed Ginocchetti to work on a range of projects that champion open data. NEPA also supported Ginocchetti in getting her geographic information system professional (GISP) certification and empowers her to be a GeoMentor to young students in a local after-school program.

“I am thankful to NEPA for trusting my geospatial capabilities and embracing my desire for open data,” she said.

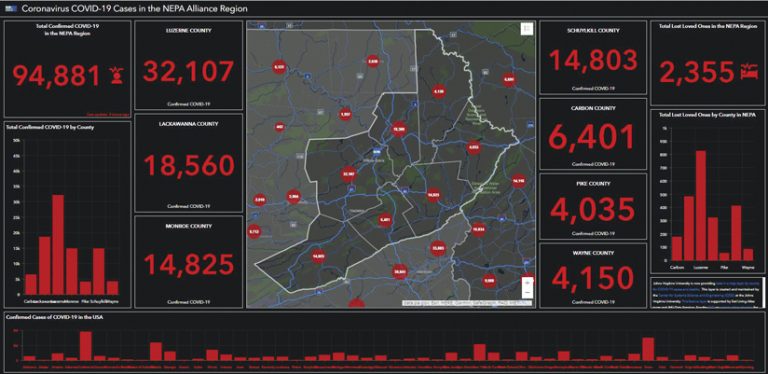

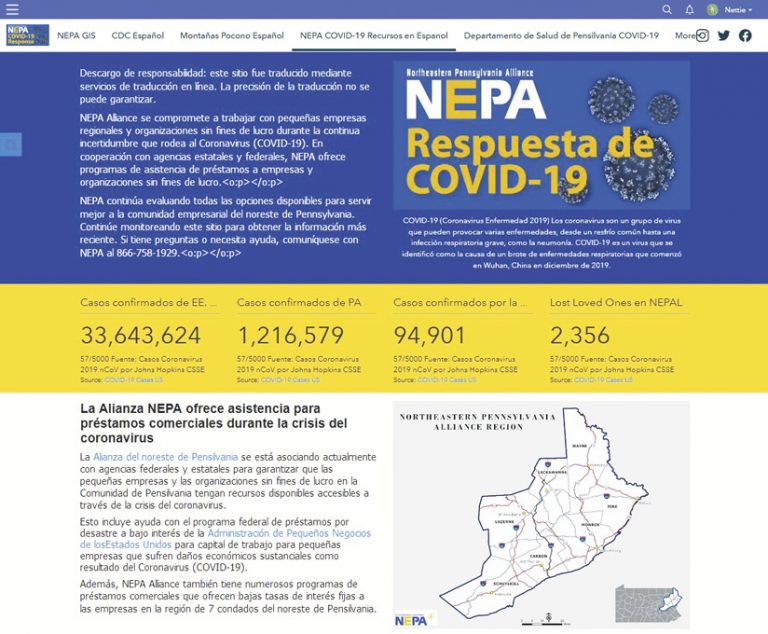

One of her standout undertakings at NEPA was creating its COVID-19 response hub. In addition to posting COVID-19 case and lost loved ones numbers, the site provides local businesses with information regarding economic assistance.

“When COVID-19 hit, our CEO said, ‘We need to get something on our web page.’ But our IT manager said we couldn’t do that because our website was so out-of-date,” Ginocchetti recalled. “And I was like, ‘Wait, I can do it.’”

It was the first time Ginocchetti had worked with ArcGIS Hub. She used the COVID-19 template to create a localized version of Johns Hopkins University’s now-famous dashboard. She then added some pages with information about all the state- and federally funded loans that were becoming available for small businesses. When Ginocchetti heard that Spanish speakers in northeastern Pennsylvania were having a hard time figuring out what was going on with the pandemic, she reached out to Esri’s ArcGIS Hub team to see if a Spanish-language version was available. There wasn’t one, but the team started working on it right away. In the meantime, Ginocchetti put her whole hub site, paragraph by paragraph, into Google Translate to at least get some Spanish-language information out.

“The day Esri released a translator tool was the day I finished my Spanish-language page,” she recalled with a laugh. She promptly replaced her version with the Esri tool.

Since then, Ginocchetti has continued to innovate with ArcGIS Hub. For example, NEPA’s CEO wanted members to be able to sign up for the organization online. But Ginocchetti didn’t want to just give members a receipt; she wanted to collect their information and put them on a map. So she added a Membership page to her hub site that employs ArcGIS Survey123 to gather members’ data and uses PayPal to allow them to pay their dues.

“Nettie is a creative thinker who is always willing to try new things,” said Brenda Wolfe, Esri’s lead product manager for ArcGIS Hub. “When she faces a challenge—like needing to translate a website or bring together ArcGIS apps with other technology—she finds novel ways to get the job done. And in the course of doing that, her enthusiasm for GIS inspires others.”

“I’m just motivated to pursue my mappiness,” said Ginocchetti—something she encourages others to do in her emails, social media posts, and other correspondence. “Where in the world would I be without GIS? I honestly don’t know.”