June 25, 2024 |

October 10, 2024

Following is a condensed version of the Preface of a new book available from Esri Press.

When I started this book, I never dreamed I’d be writing about mapping technology that protects democracy in a former Soviet state, flying wingman a mile high for a geographic information system (GIS) version of R2-D2, or meeting leaders mapping out the balancing act between conservation and development in Africa.

I didn’t expect to be writing about the Cuban Missile Crisis, Princess Diana’s stroll through an actual minefield, or the boss everyone in GIS wants—the one whose first question is “Where are the maps?”

They’re all in The Geography of Hope, and I’m looking forward to sharing the real-life stories of optimists mapping a better world.

I went into this book knowing I was writing about what a friend and many in the GIS industry call “the most important technology that people have never heard of.”

People who knew GIS gushed about how it made them and their organizations smarter or richer. But most people I told about the book didn’t know GIS technology.

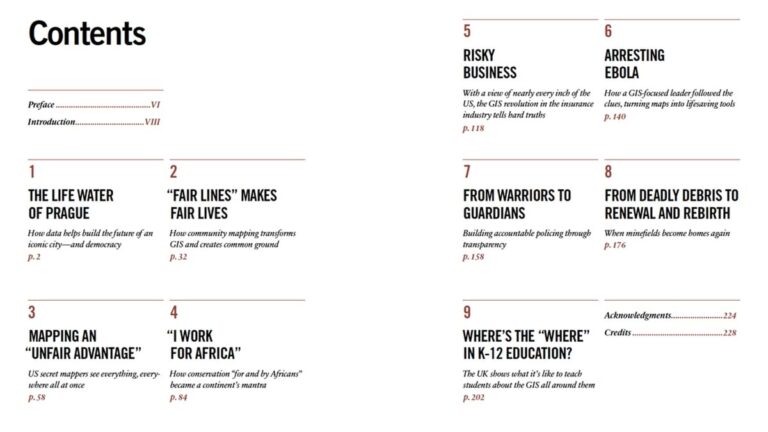

But GIS has never been just about the technology for me—and it doesn’t have to be for you. The Geography of Hope, shows how GIS helps people, communities, and organizations succeed and prosper. GIS is a toolkit—and we’ll dip into some of that, but the nine very different chapters in this book have a common thread: the choices exceptional people have made about how to use GIS tools to change the world.

GIS drives the maps on our phones. It helps trains run on time, shipping companies deliver billions of packages, police departments focus their patrols; it makes militaries more effective and enables cities to identify long-neglected disparities. Oh, and there’s the water we drink, the ability to find the petroleum that ends up in almost everything, and discovering the right places to put solar and wind power. If those don’t hit close enough to home, you can probably thank GIS for the fresh avocados that your restaurant has in the kitchen for dinner.

GIS offers great career options. GIS professionals work for governments of all sizes, builders, planners, law firms, and police and fire departments. Phone companies, utilities, investment firms, technology companies, and nonprofits all hire GIS experts. More than 55 years after its debut, the technology is just hitting its stride. And artificial intelligence (AI) is already making GIS even more useful. That’s because GIS technology is built to see the world’s patterns, not just its data points. AI can help recognize those patterns at blazing speeds. And the organizations that use GIS across all their functions—what’s known as enterprise GIS—get the most out of it.

After reporting on spies, community builders, and insurance executives, I’ve seen how GIS can be used for good, to create or share wealth and opportunities. Or not. It is subject to embedded historical, political, and cultural biases. And to be sure, GIS can be part of the growing suite of tools that undermine our privacy.

So, here’s how we decided what to include.

My initial framework for screening chapter possibilities was to follow Esri’s organizational and market verticals.

The goal was to find organizations and people who would represent hundreds or thousands of others in similar fields across the world.

I had three criteria: Which organizations reflect the best practices within their sectors? Do their leaders have interesting stories to tell? Are they topical and timely?

That helped winnow the field, but in the end, the stories that demonstrated creativity won out. I think it’s the most undervalued quality in most organizations. Some examples: I did a double take when I first saw a video about how the insurance industry decided to make high-quality images of every nonmilitary inch of the continental United States and Hawaii. Transforming a stodgy sector like insurance was a big, creative idea.

I wanted to profile Prague’s GIS team because they’re large and respected, and I’d seen their edgy work around climate change. What I couldn’t have expected in a million years was that Prague’s GIS network was not just democratizing data, it was democratizing democracy.

I’d heard about the use of GIS in the explosives-removal world; I was gobsmacked to find a gender equity story at the heart of that.

I knew GIS helped manage supply chains and increased profits, but reducing the costs of assessing a hurricane-damaged building from $12,000 to $8? Why wouldn’t every insurance company invest in a technology like that?

In Tanzania, Fortunata Msoffe built a GIS network to manage the entire national park system. Leaders from across Africa flock there to learn its secrets. And now she’s risen to a national position where she can build a system that could run everything related to tourism, a third of her country’s economy.

Because GIS exists to make connections, the stories in our chapters touched one another in unexpected ways.

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, super-secret spies you’ll meet in chapter 3, shared unprecedented online access to its imagery to help the UN’s World Health Organization map West Africa during the Ebola crisis in 2014–2015, in chapter 6.

Phone apps designed for remote data entry of Ebola cases became the apps that explosives experts use in the valleys of Afghanistan in chapter 8. They’re also the same tools Berkeley’s police use in chapter 7. The US Census Bureau, a part of chapter 2, is talking with the insurance industry to use the imagery we write about in chapter 5.

I told teacher Jacquie Black, whom you’ll meet in chapter 9, about the chapter on demining, how the sector’s leaders emphasize what comes after: renewal and return to homelands. She instantly related that back to her classroom near Edinburgh: “I get that question so often from kids whenever we talk about migration, horrible things happening like volcanoes and tsunamis, and they always ask me, ‘But why do they not just leave?’ And they just don’t understand that draw to come home.”

I didn’t really, either, until I got to know the people who devote their lives to making places safe again. It’s been a privilege to learn from them, and from all the folks who shared their stories for this book. My world has expanded at a time when COVID-19 and other factors conspired to constrict it.

I asked former spy and geospatial intelligence expert Keith Masback (you’ll meet him in chapter 3) about the future of GIS. He said, “This is our moment. If you are a geospatial person, you have hit the lottery. You’ve got to do the work to keep growing, moving … and leading the way in this location-based economy because you have been dealt a great hand. It is all about how you play it.”

That seems like a good place to end—and to begin. I hope you enjoy The Geography of Hope.

Visit the book’s companion site to read excerpts from each chapter and learn about the extraordinary people profiled in the book. You can receive a 30% discount on IndiePubs using the promo code HOPE30 at checkout. Available for purchases and shipping in the US and Canada through June 30, 2025.

June 25, 2024 |

July 18, 2024 |

November 21, 2022 |