A quarter of a century after first addressing the Esri User Conference, entomologist Edward O. Wilson returned to the plenary stage in 2019 to promote the Half-Earth Project, a conservation effort supported by Esri.

In nearly a century of living and studying living things, Wilson has undoubtedly seen more ants than the busiest professional bug exterminator. Placing the words ants and exterminator together in a sentence in an article about Wilson could strike a nerve among people with an affinity for ants. As a man who has studied ants for most of his life, it’s not surprising that one of the most common questions Wilson gets asked by people is what to do about the ants that crawl into their houses. Spray? No way!

“They are missing some of the wonders of nature,” Wilson insisted. “I love having a colony of ants in my kitchen. What I do is I give them something to eat [like] cookie crumbs.”

Once, a colony took up residence near Wilson’s kitchen sink. “They would come out of a crack in the base of the edge of the sink. Instead of spraying them or squishing them, I would put food out for them and watch,” he said. “The scout would come out and smell and then he would eat a little bit and then he would [get] all excited. It would go running back, laying a little trail and, in a few minutes, out would come a whole bunch of ants out along the trail. I enjoyed having a pet colony. I recommend it.”

As a teenager, Wilson reported the first known colony of imported red fire ants in his home state of Alabama. Later, he studied the warrior-like Matabele ants in Africa, the critically endangered Aneuretus simoni in Sri Lanka, and thousands of other species. Several of his 32 books focus on the ant world, including The Ants [coauthored with Bert Hölldobler], which won a Pulitzer Prize, and his only work of fiction, Anthill: A Novel.

In the late 1950s, Wilson made what he considers his single most important discovery: pinpointing which gland in ants gives them the ability to communicate with each other.

“When I made it, I couldn’t sleep that night—that kind of a discovery,” Wilson recalled. “I knew that ants communicate, not by touch—there isn’t any signaling something—not by any sound—but by chemicals—pheromones, that is, odors that they would release, substances they would spread from a gland that would give a message to other ants. That was only vaguely thought when I decided to check this all out and see if I could break the pheromone code.”

Using fire ants for his experiment, Wilson tested different glands with no luck until he extracted the Dufour’s gland at the base of the sting.

“I had noticed when the fire ants find food and return home they stuck out their sting and were dragging their sting,” he said. “[Dufour’s] was a little teensy gland that took really a lot of effort to dissect out. But when I took it out and made an artificial trail with it, I could lead fire ants anywhere I wanted.”

It was an amazing sight to the young entomologist. “The fire ant would discover food, come running back, laying a trail, rush into the nest, and then rush up to other fire ants—almost like grabbing them by the shoulder and shaking them and saying “Food, food, I found food! The ants smell the trail and get on the trail, and they run back.”

Right now, Wilson’s research focus is on ecosystems. Little research has been done on them. But their importance is inescapable. [Read the accompanying article “The Half-Earth(ling)” to learn more about Wilson’s Half-Earth Project.]

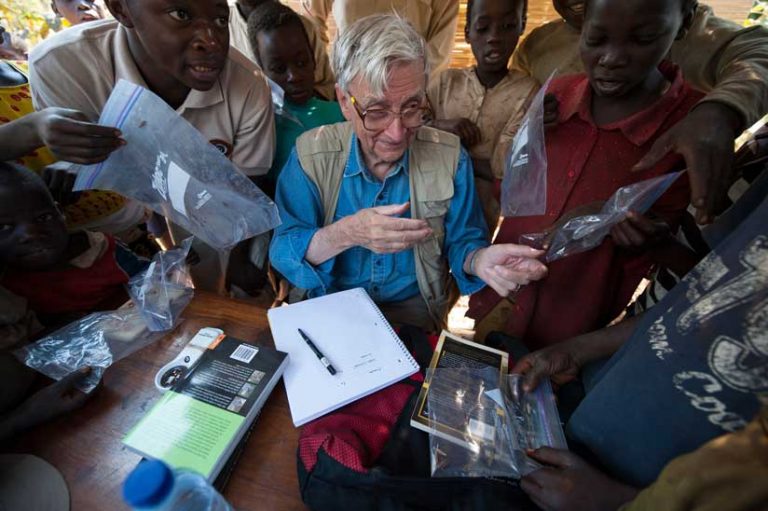

Much more data on plant and animal species needs to be collected, both by scientists and citizen scientist volunteers, according to Wilson. He recently celebrated his 90th birthday by participating with taxonomic specialists, students, families, and other community members in the Great Walden BioBlitz at Walden Woods in Massachusetts. Wilson made a special point of spending time with a group of children collecting samples of organisms, including ants.

Wilson likes to use the example of the ecosystem of the sea otter, which was hunted to near extinction on the Pacific Coast by the early 1900s. When the sea otter population fell, the kelp forests along the coast disappeared too. That threw an entire ecosystem off kilter.

“The kelp forest of seaweed and algae along the coast declined and, in places, disappeared,” Wilson said. “What had happened? The sea otter fed upon sea urchins that live in kelp forests. The sea otter was the [urchins’] main predator. The sea urchins exploded in population. They did not have their predator that kept them in control. There were so many of them that they ate the kelp. When sea otters were allowed to come back—hunting was forbidden—then the sea otters reduced the numbers [of sea urchins], and now the kelp is coming back.”

Wilson said not much is known about ecosystems, but he hopes to change that. “What I am doing right now is to begin systematic studies, deep studies, mathematical studies of ecosystems,” he said. “It’s so complex; nobody understands them.”

He wants to find out how ecosystems are formed, how they evolve, and then how they equilibrate. “A pine forest has been there for a thousand years. How did [the trees] come to a point where they don’t change much?” he asked.

It’s a tall order, but Wilson is never one to slow down. “I’m 90 now, so I’ve got to get this done before I pass on to that great rain forest in the sky,” he said with a smile.