Janice Thomson: Tireless Wilderness Advocate

GIS Hero

![]() An avid hiker who adores the mountains of the Northwest, Janice Thomson was drawn to The Wilderness Society out of a desire to defend the wildlands she loves. In her current position as the society's director for the Center for Landscape Analysis, Thomson integrates a wide variety of data items into spatial analyses and tenable maps. These maps are then used to promote the goals and values of The Wilderness Society to agencies working directly with the land. As a lifelong wilderness advocate, Thomson has put her passion to work protecting America's public lands.

An avid hiker who adores the mountains of the Northwest, Janice Thomson was drawn to The Wilderness Society out of a desire to defend the wildlands she loves. In her current position as the society's director for the Center for Landscape Analysis, Thomson integrates a wide variety of data items into spatial analyses and tenable maps. These maps are then used to promote the goals and values of The Wilderness Society to agencies working directly with the land. As a lifelong wilderness advocate, Thomson has put her passion to work protecting America's public lands.

Janice Thomson

Cofounded in 1935 by renowned wildlife ecologist Aldo Leopold and several other prominent conservationists of the time, The Wilderness Society has a mission to "protect wilderness and inspire Americans to care for our wild places." The Wilderness Society works to protect the United States' 635 million acres of national public lands. Among other conservation actions, the organization has led the effort to permanently protect as designated wilderness nearly 110 million acres in 44 states to date. Thomson's ability to infuse these efforts with geospatial intelligence makes her integral to achieving these objectives.

Thomson received her master's and PhD degrees in geology from Dartmouth College. After graduating, she went to work for Lockheed Engineering and Sciences, mapping land cover in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. After a year and a half with Lockheed, Thomson started her journey with The Wilderness Society in 1992.

Much of Thomson's work centers on habitat degradation sometimes associated with the extraction of fossil fuels, especially oil and gas. By applying spatial analysis to the relationship between oil and gas infrastructure and various natural resources, Thomson is able to create maps that are, in turn, used to craft development recommendations. These recommendations, made through the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), promote optimized solutions that integrate oil and gas industry development plans with strategies for protecting the land's ecological and wilderness values.

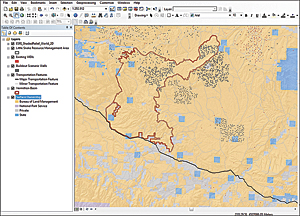

Build-out scenarios, like this one of the Vermillion Basin, illustrate development plans and help predict habitat impacts.

"We provide the best science possible and advocate strongly for lands that should be protected from development, and we provide recommendations for how other lands can be developed in ways that minimize ecological impacts," says Thomson.

The vast interdisciplinary cooperation required for development in the oil and gas industry makes the merging of information into a viable recommendation no small feat. Couple a complex industry with conservation goals and the delicate interdependence of wild ecosystems, and the task of providing sound counsel to all the stakeholders becomes even more daunting. This is where Thomson comes in. She takes natural resource datasets and industry development plans that are impracticable alone and combines them to create functional maps that expand organizational awareness. This increased understanding is crucial to facilitating sustainable development in the oil and gas industry.

"The Wilderness Society is an organization that integrates science, policy, and advocacy," says Thomson. "Our integrated approach allows us to bring unique GIS analyses to the table to answer questions that maybe other government agencies or entities aren't asking. We're then able to share that information with all the players involved in a given project—people like county commissioners, conservation partners, and oil and gas professionals."

The staggering diversity of wildlife poses a critical challenge for future development. "The effect of habitat fragmentation varies tremendously by species; that's why this work is all done on a species-by-species basis," says Thomson. "We use studies completed by field biologists who have measured the responses of different wildlife species in proximity to oil and gas development, and fortunately, some of these biologists are publishing information about spatial metrics that we can measure using GIS."

By integrating biological literature with spatial data, Thomson was able to illustrate and compare development with mule deer migration routes in the Upper Green River valley. Her efforts resulted in accessible analytic data that demonstrated the impact of infrastructure development on mule deer. This data was put to use to create specific setup recommendations BLM could use for future development plans.

Another way that Thomson encourages environmental consideration is by creating build-out scenarios of roads and well pads and providing informed projections of the impact on local species. "We give people a qualitative picture and quantitative story," says Thomson. "These projections are really powerful to bring to the table at a meeting with county commissioners, the BLM, and any other local stakeholders. Projections allow us to illustrate what the scenario they're supporting would look like on the ground and what its likely impacts would be on the important species in the region."

The employment of a similar build-out scenario contributed to a recent win for The Wilderness Society. After years of discussion surrounding potential land management plans for the Little Snake resource area in northwest Colorado, The Wilderness Society presented a build-out scenario demonstrating how proposed oil and gas development would affect the Little Snake area. A particular area of concern was Vermillion Basin, an area of northwest Colorado with profound wilderness character and value to locals. When the final management plan came to fruition, the Vermillion Basin was granted administrative withdrawal of oil and gas development.

Thomson knows that a well-crafted map has the capacity to advocate certain development methodologies simply by being available for consideration. With this function in mind, she puts relevant maps in front of decision makers.

"Creating a map about a particular resource and getting it into the hands of stakeholders often gets the map into closed-door meetings," notes Thomson. "The map can then be a voice when someone from our staff is not able to be a voice."

Thomson works courageously to promote engagement with wildlands and understanding of the tremendous value that these lands hold. "GIS helps connect people with the land," Thomson says. "These lands provide vital services to communities, whether it's clean water and air, income from recreational visitors, cultural values, or spiritual significance. It's really exciting to represent these values on maps to allow people to share their own accounts and why they believe land needs to be protected." Her tireless work advocating for wilderness has made Janice Thomson a true GIS hero.

For more information, contact Janice Thomson, director of the Center for Landscape Analysis, The Wilderness Society (e-mail: janice_thomson@tws.org).