Strengthening the GIS Profession

David DiBiase, Director of Education, Industry Solutions, Esri

Is GIS a profession? If so, what's its relationship to other professions in the geospatial field? How can you tell if someone who calls herself a GIS professional—or a GIS educator for that matter—knows what she's doing? You might be surprised to learn that these are contentious questions in the United States and other parts of the world. They're contentious because the demand for GIS work has surpassed the demand for other kinds of geospatial work, despite the fact that GIS is a relatively new branch of the field. The rightful roles and qualifications of GIS pros are in dispute, and there's competition for who gets to decide.

Is GIS a profession? If so, what's its relationship to other professions in the geospatial field? How can you tell if someone who calls herself a GIS professional—or a GIS educator for that matter—knows what she's doing? You might be surprised to learn that these are contentious questions in the United States and other parts of the world. They're contentious because the demand for GIS work has surpassed the demand for other kinds of geospatial work, despite the fact that GIS is a relatively new branch of the field. The rightful roles and qualifications of GIS pros are in dispute, and there's competition for who gets to decide.

Do you consider yourself a GIS professional? Or are you thinking of becoming one? By GIS professional, I mean someone who makes a living through learned professional work (see table below) that requires advanced knowledge of geographic information systems and related geospatial technologies, data, and methods. If that's what you do, or what you might want to do, then you have a stake in the dispute. Your right to make a living doing GIS work, your ability to be part of an open and innovative GIS community, and your chance to be part of something big that's making a difference in the world all depend on how those contentious questions are answered.

The work roles of three geospatial professions cross boundaries of the geospatial industry sectors and overlap one another. Each profession has a "center of mass" within one sector. Not all geospatial professions are depicted.

I've been interested in the professionalization of GIS work since Bill "Hux" Huxhold and others raised these questions in the 1990s. Hux was, and is, a respected member of the GIS old guard. With his piercing blue eyes and close-cropped white hair, Hux looks a bit like Mr. Clean with eyeglasses. But unlike that cheerful ally of housekeepers everywhere, Hux was mad in the late 1990s, and he wasn't going to take it anymore.

Hux was angry that there were no standards to ensure the qualifications of GIS professionals. "Can it be," he asked, "that anyone can pass himself off as a 'GIS professional'?" Hux also railed at the absence of a formal quality control mechanism for GIS education. "Can it be that anyone can pass herself off as knowing what to teach GIS students?" To fill these gaps, Hux, Nancy Obermeyer, and a few others crusaded for a formal professional certification program for GIS professionals. Hux convinced the Urban and Regional Information Systems Association (URISA) to establish a certification committee to study the problem and recommend a solution. He also argued for a formal accreditation program for GIS in higher education.

Creating the GIS Profession

I was an educator at Penn State University at the time, and these arguments made a strong impression on me. Like many other educators, I was skeptical about the potential of certification and accreditation to ensure competence and quality. But the more I read and thought, I became convinced something more than competence is at stake. What's at stake in the professionalization of GIS is the right of GIS practitioners—some of whom are my students—to work side by side as respected peers with other geospatial professionals.

From the time that the US Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration (DOLETA) showcased geospatial technology as a high-growth industry, it warned that the absence of a coherent definition and public awareness of the field posed an obstacle to its growth. As the philosopher Michael Davis said, "Just as nobody likes a wise guy, nobody likes a definition" (2002). But to define something is, in a sense, to create it. I believe that the early crusaders and their successors have helped create a flourishing GIS profession that is just now coming of age.

The Geospatial Work Force

Until recently, we had to be content with anecdotal evidence about the GIS profession's size and scope. Reliable estimates of GIS employment didn't exist in the United States or most anywhere else. However, the anecdotal evidence was enough to worry DOLETA and others that work-force needs were growing faster than the capacity of the geospatial education infrastructure. Good students tended to get good jobs. Then confidence waned somewhat during the recession, when good jobs of every kind became much harder to find and keep.

The size and scope of the GIS work force came into sharper focus when DOLETA established two new GIS occupations—geographic information scientists and technologists and GIS technicians—in late 2009 and when it identified the core competencies of geospatial professionals in 2010. Along with the new occupation definitions came the first rough estimates of the size and growth of the US GIS work force.

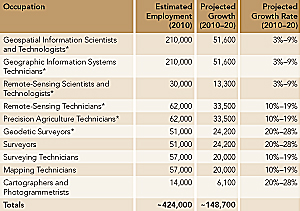

Estimated 2010 US employment for 10 geospatial occupations, along with projected employment growth through 2020. (Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, available at onetonline.org)

The employment estimates and growth projections in the accompanying table don't add up because some estimates overlap. However, even when the overlaps are accounted for, the estimates are still impressive: nearly 425,000 geospatial professionals were employed in 2010 in the United States, DOLETA work force analysts say, and almost 150,000 additional positions will be created by 2020. Significantly, the two GIS occupations account for the largest share of those employment estimates—about half of all US geospatial workers in 2010, and nearly more than one-third of new positions to be created by 2020. Estimates of the size of the geospatial work force beyond the United States are harder to find, but some reckon that there were about two million professional GIS users worldwide in 2005 (Longley et al. 2005).

Meanwhile, GIS employment prospects are good in many locations. According to Richard Serby, president of GeoSearch Inc., a leading personnel recruitment firm specializing in the geospatial industry, employment opportunities in most sectors have already rebounded to prerecession levels in the United States, recovering faster than most other industries. Serby points out that Indeed.com, which aggregates job postings worldwide, listed more than 11,000 geospatial jobs just for the period February 15 to March 15, 2012. Half of the geospatial jobs had GIS in their titles, and all but a few jobs included GIS in their requirements.

Scoping the GIS Profession

In 2010, DOLETA issued a Geospatial Technology Competency Model (GTCM) that identifies the specialized knowledge and abilities that successful geospatial professionals possess. The GTCM is useful for geospatial workers, who can use it to guide their continuing professional development plans. Employers can use it for job descriptions and interviews. Students can use the GTCM to assess what they know, what they need to learn, and which educational programs fit their needs. Educators can use it to assess how well their curricula align with work force needs. And certification and accreditation bodies can use it as a basis for their requirements. The GTCM is freely available for use and reuse, without restriction, at www.careeronestop.org/competencymodel.

In addition to 43 essential competencies common to most of the geospatial occupations, the GTCM identifies 19-24 essential competencies for each of three industry sectors: positioning and data acquisition, analysis and modeling, and software and application development. The sectors represent "clusters of worker competencies associated with the three major categories of geospatial industry products and services." The diagram above shows the scope of responsibilities for three geospatial professions in relation to the industry sectors and to one another.

Debates about the rightful roles of GIS professionals arise because their activities tend to overlap those of other geospatial professions. Overlaps cause tensions but also afford opportunities for cooperation. J. Alison Butler, an experienced and outspoken champion of the GIS profession, points out that overlaps tend to be complementary. For example, professional surveyors and GIS professionals do many similar things but usually at different geographic scales ("Surveyors work at a 1:1 scale," Butler says, in contrast with GIS professionals, who "work at smaller scales and do not need to be so precise."). And although professional roles overlap, each geospatial profession exhibits a distinctive "center of mass," or concentration within one sector (see diagram above).

The GIS profession's center of mass is analysis and modeling. GIS professionals tend to be end users of geospatial data and software. They're employed in a wide range of allied industries, such as natural resources, government, and defense and intelligence. The character and geographic distribution of GIS employment differs from one industry to the next. However, the core responsibility of most GIS professionals is to use specialized software technology to render actionable information from geospatial data. In addition, many GIS professionals also acquire and process geospatial data (within the constraints of government regulation over data collection activities that pose risks to public safety and welfare). Others design and implement geospatial databases or develop customized software applications.

In this article, I define GIS professional narrowly, as one who makes a living doing GIS work. Some object to scoping the field so narrowly. Directions Media editor in chief Joe Francica points out that "non-GIS people are becoming more 'location aware' and thinking spatially." Gone are the days, Francica and others observe, when knowledge workers had to rely on "the map guy" to provide location-based information. Now "everyone is becoming a 'map guy.'" Even so, neither widespread access to mapping capabilities nor crowdsourced or "volunteered" geographic information have displaced GIS professionals. On the contrary, as the employment estimates above suggest, the demand for GIS professionals seems to be increasing even as location awareness proliferates.

GIS as a Learned Profession

Not everyone agrees that a GIS profession exists. Debates about whether GIS qualifies as a true profession date back more than 20 years. Today, however, by almost any definition, there's not much room left for debate. Consider, for example, the definition of learned professional in the US Department of Labor's Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). To qualify as a learned professional under FLSA, a worker's primary duties must require advanced knowledge, involving the "exercise of discretion and judgment." Advanced knowledge "must be in a field of science or learning" (comparable to the traditional professions of medicine, law, theology, accounting, engineering, teaching, and others) and "must be customarily acquired by a prolonged course of specialized intellectual instruction."

Not everyone agrees that a GIS profession exists. Debates about whether GIS qualifies as a true profession date back more than 20 years. Today, however, by almost any definition, there's not much room left for debate. Consider, for example, the definition of learned professional in the US Department of Labor's Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). To qualify as a learned professional under FLSA, a worker's primary duties must require advanced knowledge, involving the "exercise of discretion and judgment." Advanced knowledge "must be in a field of science or learning" (comparable to the traditional professions of medicine, law, theology, accounting, engineering, teaching, and others) and "must be customarily acquired by a prolonged course of specialized intellectual instruction."

Advanced Knowledge

The advanced knowledge that distinguishes the GIS profession is now well defined. The first comprehensive attempt to specify the knowledge that characterizes the broad geospatial field was the University Consortium for Geographic Information Science's (UCGIS) Geographic Information Science and Technology Body of Knowledge (2006). Building on that foundational work, DOLETA issued the GTCM in 2010. As discussed above, DOLETA also provides detailed descriptions of 10 geospatial occupations, including geospatial information scientists and technologists and geographic information systems technicians.

Specialized Education

Formal, specialized education is commonly included in GIS job requirements and is required for GIS professional (GISP) certification. Many thousands of students now pursue specialized certificates and degrees in GIS at colleges and universities worldwide. Some 7,000 colleges and universities worldwide—including over 85 percent of the institutions included in The Times of London's ranking of the top 400 institutions—maintain low-cost education licenses of Esri's ArcGIS software. And since Esri made free, one-year educational software licenses available for individual student use in fall 2005, over 450,000 students worldwide have requested DVDs or downloaded the software. The availability of no-cost ArcGIS software that students can use on their personal computers has helped educational institutions offer advanced GIS education online for adult learners who can't put their lives on hold to participate in traditional campus-based education.

GIS seems clearly to qualify as a learned profession under the FLSA definition. The advanced knowledge that distinguishes the profession is well defined. Prolonged courses of specialized intellectual instruction are widely available, attracting large and increasing numbers of enrollments.

Professional Ethics in GIS

Professions are more than just occupations, and the distinction involves more than just specialized knowledge and education. One of the distinguishing characteristics of a profession is its specialized code of professional ethics.

In the early 1990s, Will Craig—another pioneer of urban and regional information systems and GIS—pointed out the need for a code for the GIS profession and set out to write one. Craig began by examining the existing codes in use in other fields. He found "surprising similarity" among them. Most reflected a "duty-" or "obligations-based" approach to ethics. "Obligations to society," he observed, "usually override other considerations" in the codes he studied. At its founding in 2004, the GIS Certification Institute (GISCI) endorsed the GIS Code of Ethics he completed (with help from many members of the GIS community) and later developed its own complementary Rules of Conduct. To qualify for certification as a GISP, applicants must pledge to uphold the code and rules. Coming to terms with its ethical challenges is another sign of a profession that is coming of age.

Certification and Licensure

Another distinguishing characteristic of professions is specialized certification or licensure. We typically think of these as mechanisms to ensure that individual practitioners are competent and trustworthy. However, another way to think about certification is as a road map for continuing professional development. GISCI has conferred its GISP certification on more than 5,000 professionals who document sufficient formal education, experience, and contributions to the profession. To qualify for renewal of certification, GISPs must document continuing formal education and contributions. These requirements strengthen the profession by ensuring that professionals "keep current in the field through . . . professional development" (GIS Code of Ethics Item II. 1.).

Unlike the state licensure required for professional surveyors in the United States, GISP certification remains voluntary (though one state, South Carolina, requires that surveyors who use GIS be licensed as "GIS surveyors"). In part, this difference is due to the fact that GIS is a much younger profession than surveying. However, recent developments suggest that GIS certification may not remain voluntary for long. According to Max Baber of the US Geospatial Intelligence Foundation, the US undersecretary for defense intelligence has mandated a formal policy for certification of geospatial analysts. The policy is to be in place at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency by September 2012. Baber believes that GIS professionals in the civilian side of government may be affected in the longer term. It appears that GIS certification is finally taking root.

GIS Professional Organizations

Another characteristic of GIS and other professions is specialized membership organizations dedicated to advancement of the profession. Such organizations typically aim to serve members through continuing professional development opportunities and through advocacy on their behalf in the policy arena. (A list of organizations for geospatial professionals is available at edcommunity.esri.com.) Voluntary, active participation in such organizations is one example of what GISCI means by "contributions to the profession."

Toward a Moral Ideal for GIS

The GIS field has all the trappings of a profession, including a distinctive body of advanced knowledge, specialized educational offerings, a code of professional ethics, mechanisms for professional certification, and specialized membership organizations. What's lacking is a certain ethos—a characteristic spirit evident in the shared beliefs and aspirations of mature professions like medicine, the law, and even accounting. Darrell Pugh, the author so often cited for his checklist of the defining traits of professions, includes one he calls a "social ideal." For Michael Davis, serving a shared "moral ideal" is a defining characteristic of all professions. Physician and ethicist John W. Lewis argues that a profession's "core product and service is [its] pledge to put the interests of others ahead of [its] own while providing [its] specific services." At the 2012 Esri Partner Conference, Jack Dangermond reminded attendees "we have a driving purpose to make a difference in the world."

How can the GIS profession advance society's interests? What is the GIS profession's moral ideal? For starters, here's my suggestion:

- The GIS profession's moral ideal is to apply geospatial technologies and spatial thinking to design sustainable futures for people and places everywhere.

Challenges

The GIS profession is relatively young. It has weaknesses and faces some very real threats. Some critics question the profession's legitimacy, citing the facts that GIS professional certification remains voluntary and that no formal GIS accreditation process is in place to hold colleges and universities accountable. Others seek to monopolize the use of GIS and related technologies through government regulation. Given these challenges, GIS professionals need to do everything we can—individually and collectively—to strengthen our profession.

Seven Things Every GIS Professional Can Do to Strengthen Our Field

- Become certified as a GISP or its equivalent (depending on where you are and what you do). Professional certification is a public commitment to competence, ethical practice, and continuing professional development. (Technical certifications like Esri's are valuable, too, but are no substitute for professional certification.) Formalizing that commitment, and fulfilling it throughout your career, is one of the most significant things you can do to strengthen your profession. And the larger your GIS professional community grows, the better your chances to control your own destiny.

- Map out a professional development plan that includes continuing formal education and contributions to the profession. Whether you opt in to certification or not, use the requirements for renewal of GISP certification—and the GTCM—as guides.

- Join and be actively involved in one or more organizations that advance the interests of the GIS profession. Wise employers will help support your participation. If you don't enjoy such support in your job, participate anyway and look for a better job.

- Be able to explain the nature of your profession, its history, and its code of ethics.

- Cultivate respectful working relationships with colleagues in kindred professions. Participate in efforts to increase cooperation among the geospatial professions but stand up for your profession when its legitimacy is challenged. Keep in mind that your adversaries are usually not your professional colleagues but rather the lobbyists and lawyers who stand to gain the most by monopolistic regulations.

- Volunteer for GIS activities that benefit society. Help increase public awareness on GIS Day. Become a mentor for a schoolteacher who wants to teach with GIS. Volunteer to serve on an industry advisory board for a GIS certificate and/or degree program at a nearby higher education institution. Encourage such programs to use the GTCM to assess their curricula and students and to embrace accreditation.

- Articulate a "moral ideal" for GIS that expresses your professional commitment to society.

So, what's your moral ideal?

About the Author

David DiBiase is Esri's director of education industry solutions. Before joining Esri in 2011, he founded the Penn State Online master's degree and certificate programs in GIS. As a member of URISA's Certification Committee, he helped design the criteria by which more than 5,000 GISPs have been certified. He is a past president of GISCI.

For more information, contact David DiBiase (e-mail: ddibiase@esri.com).

References

Butler, J. A. (2008). "Redefining Who We Are." Professional Surveyor Magazine, April. www.profsurv.com/magazine/article.aspx?i=2117.

Davis, Michael (2002). Profession, Code, and Ethics. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

GIS Certification Institute. Code of Ethics and Rules of Conduct. www.gisci.org.

Lewis, John W. (2001). Ethics and the Learned Professions (white paper). The Institute for Global Ethics. www.globalethics.org/files/wp_professions.pdf/20.

Longley, P. A., M. F. Goodchild, D. J. Maguire, and D. W. Rhind (2005). Geographic Information Systems and Science. 2nd ed. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Obermeyer, Nancy J. (2007). "GIS: The Maturation of a Profession." Cartography and Geographic Information Science 34, no. 2: 129-32.

US Department of Labor (revised 2008). "Fact Sheet #17D: Exemption for Professional Employees Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)." www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/fairpay/fs17d_professional.pdf [PDF].