Understanding Our World

—Richard Saul Wurman

At the dawn of humankind, people made crude sketches of geography on cave walls and rocks. These early maps documented and communicated important geographic knowledge our ancestors needed to survive: What is the best way to get from here to there? Where is the water at this time of year? Where is the best place to hunt animals? Our ancestors faced critical choices that determined their survival or demise, and they used information stored in map form to help them make better decisions.

Early man used cave walls and rocks to communicate and share geographic knowledge.

Fast-forward to the 1960s. The world had become significantly more complex than it was for our early ancestors, and computers had arrived on the scene to help us solve increasingly complex problems. The 1960s were the dawn of environmental awareness, and it seemed a natural fit to apply this powerful new computer technology to the serious environmental and geographic problems we were facing. And so the geographic information system (GIS) was born.

Today, GIS has evolved into a crucial tool for science-based problem solving and decision making. People who use GIS examine geographic knowledge in ways that would be extremely time-consuming and expensive when done manually. The map metaphor remains the dominant medium for sharing our collective geographic intelligence, and development of a GIS-based global dashboard will lead to a revolution in how we understand our world and plan for the future.

Geographic Knowledge Leads to Geographic Intelligence

Geographic knowledge is information describing the natural and human environment on earth. For our ancestors, geographic knowledge was crucial for survival. For our own survival, geographic knowledge plays an equally fundamental role. The biggest differences between then and now are that our problems are much more complex, and the sheer volume of data—of geographic knowledge—at our disposal is daunting. And whereas passing down geographic knowledge in the past was limited to a few cave paintings or rock drawings, GIS technology now enables a collective geographic intelligence that knows no spatial or temporal bounds.

Today we have more geographic data available than ever before. Satellite imagery is commonplace. Scientists are producing mountains of modeled data. And an ever-increasing stream of data from social media, crowdsourcing, and the sensor web are threatening to overwhelm us. Gathering all this information—this geographic knowledge—and synthesizing it into something actionable is the domain of GIS. More data does not necessarily equate with more understanding, but GIS is already helping us make sense of it, turning this avalanche of raw data into actionable information.

Human-Made Ecosystems

Our traditional understanding of ecosystems as natural landscapes is changing. Anthropogenic factors are now the dominant contributor to changing ecosystems. Human beings have not only reshaped the physical aspects of the planet by literally moving mountains but also profoundly reshaped its ecology.

And it's not just landscape-scale geographies that can be considered human-made ecosystems. In modern society, buildings are where we spend the vast majority of our waking and sleeping hours. Our facilities are themselves man-made ecosystems—vast assemblages of interdependent living and nonliving components. Facilities have become the primary habitat for the human species, and this is changing the way we think about collecting, storing, and using information describing our environment.

A key aspect of our social evolution is to recognize the effects we have already had on ecosystems, as well as to predict what future impacts will result from our actions. Once we achieve this level of understanding, we can direct our actions in a more responsible manner. This type of long-term thinking and planning is one of the things that make humans human.

Recognition of the overwhelming dominance of man-made ecosystems also makes us cognizant of the tremendous responsibility we have—the responsibility to understand, manage, and steward these ecosystems.

Only when they care will they act.

Only when they act can the world change."

—Dr. Jane Goodall

Designing Geography

We humans are no longer simply passive observers of geography; for better or worse, we are now actively changing geography. Some of this change may be intentional and planned, but much of it is unintentional—"accidental geography." As we grow more knowledgeable, become better stewards, and obtain a greater understanding of our world and how humankind affects it, we need to move away from this "accidental geography" and toward what Carl Steinitz calls "changing geography by design." As GIS professionals, we can accomplish this through the integration of design into the GIS workflow.

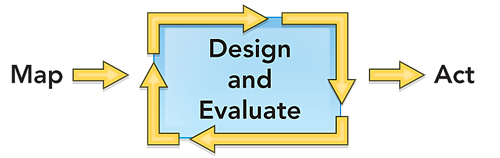

The GIS workflow starts with a decision that needs to be made. We first gather background information about the geography of that decision and organize it on a digital map. We then use the map to evaluate the decision. Once we fully understand the geographic consequences of the decision, we can act.

![]()

When an idea is proposed with geographic consequences—a housing development, a shopping center, a road, a wildlife preserve, a farm—it first goes through a design process. After it is initially designed, a project is vetted against geography using this approach.

A typical project will go through many iterations of design and evaluation. As the constraints of geography on the project—and the impacts of the project on geography—are revealed, the design is continually refined. Because design and evaluation have traditionally been separate disciplines, this phase of a project can be time-consuming, inefficient, and tedious.

What if we could reduce the time and tedium of these iterations by integrating design directly into the GIS workflow?

This integration—what we refer to as GeoDesign—is a promising alternative to traditional processes. It allows designers and evaluators to work closely together to significantly lessen the time it takes to produce and evaluate design iterations.

Bringing science into the design process without compromising the art of design will require new tools and enhanced workflows. Most of all, it will require a new way of thinking about design. And it will allow us to more easily move from designing around geography to actively designing with geography.

We must manage our actions in ways that maximize benefits to society while minimizing both short- and long-term impacts on the natural environment. GeoDesign leverages a deep geographic understanding of our world to help us make more logical, scientific, sustainable, and future-friendly decisions. GeoDesign is our best hope for designing a better world.

Toward a Global Dashboard

An important tool for understanding our dynamic planet is a global dashboard. This tool would operate as a framework for taking many different pieces of past, present, and future data from a variety of sources, merging them together, and displaying them in an easy-to-read-and-interpret format that indicates where action needs to be taken. That such a dashboard would use the map metaphor seems obvious; our long history with map representations means that people intuitively understand maps.

GIS helps provide this framework by allowing users to inventory and display large, complex spatial datasets. When people see all this geographic knowledge on a map, and they see environmental problems or economic issues in the context of their neighborhood, their street, or their house, this leads to a new level of understanding. They get it right away. The ability to take all this data and put it in context on a dynamic, personalized map is very powerful.

GIS can also be used to analyze the potential interplay between various factors, getting us closer to a true understanding of how our dynamic planet may change in the coming decades and centuries.

A better world is the common goal all of us—geographers, planners, scientists, and others—have been striving for. Although we've made a lot of progress in building the technological infrastructure to help us accomplish this monumental task, we're still not quite there yet.

I'm a firm believer that we have the intelligence and the technology—the ability—to change the world. We can make it better. We must make it better. But we first need a firm and complete understanding of our world before we act to design our future.