Hand in Hand—Spatial Information for Latin America

By Santiago Borrero, Secretary General, Pan American Institute of Geography and History

In order to better implement spatial information in developing countries, training and institutional development must go hand in hand.

In order to better implement spatial information in developing countries, training and institutional development must go hand in hand.

A good number of national development plans in Latin America prioritize education based on new technologies and state that digital illiteracy must be eradicated, as it constitutes an obstacle to access to the opportunities offered in today's globalized world. However, very little, if ever, is said about the fundamental need for spatial information, and thus the subject should be incorporated into national development plans and broad interdisciplinary processes. GIS is a key tool to critically understand geographic problems and put geographic thought into practice, especially now that citizens enjoy the benefits of instant geography through map services, dynamic photo files, and 360-degree street maps, for example.

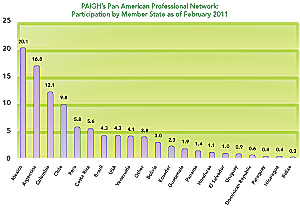

The Pan American Institute of Geography and History (PAIGH) is the oldest organization in the Organization of American States (OAS) and the one in charge of providing it with the spatiotemporal component necessary to promote the comprehensive development of the region. Among other activities, PAIGH fosters the development of spatial data infrastructure in the Americas and to that end carries out workshops and regional projects every year.

Development Is Relative and Highly Subjective

When using the term development, we are referring to a relative, extremely subjective and often contradictory concept in which what some regard as progress is often viewed by others, from an equally subjective perspective, as a setback. Take, for example, the United Nations Development Programme's annual report on global development. The 2007 report, prior to the 2008 financial crisis, asserted that the global economy was growing at a steady pace and that, in spite of increased inequality, the human development gap was in sharp decline. More recently, the 2010 report stated the world was on an inexorable path to compliance with the Millennium Development Goals, as evidenced by graphs and statistics that critics might disagree with. Personally, I feel it has been quite a feat for the United Nations to make its members agree upon an effective, well-intentioned global strategy.1

Now let's look at our region with the same magnifying glass. In 2010, a significant number of countries held bicentennial celebrations with great fanfare. One thing was made patently clear to me during the commemorations: Although the nations of the American continent are indeed young, and the economic and social progress achieved by countries such as the United States and Canada is impressive, for the great majority of our countries, the twenty-first century holds a geopolitical vision quite unlike that of the days of independence in the early nineteenth century. Nowadays, the challenges of the Pan-American movement are very different and focus on the war on poverty, climate change, the scale of natural disasters and their mitigation, management and organization of land and natural resources, development of global markets and their local impact, and the social and economic significance of knowledge. Today, the objectives of the PAIGH 2010–2020 Pan American Agenda include

- To consolidate PAIGH as a regional Pan-American forum to advance geographic information and assist with the comprehensive development of its member states

- To encourage the development of spatial databases so they can be used in decision-making processes, to make early-warning systems more efficient, and to improve disaster response times

- To identify actions that will contribute to regional integration in specific fields, such as climate change, territorial organization, and natural disasters

- To assist with development of high-quality geographic information infrastructure essential to analysis processes

To successfully deal with these challenges, information technologies, such as earth observation systems, GIS, and spatial data infrastructure, play an increasingly relevant role. Although they are revolutionary in and of themselves, from the development perspective, the same relativity I mentioned with regard to global growth could apply here as well. Take, for example, the principle of sharing and accessing spatial data through the Global Earth Observation System of Systems (GEOSS). In the short term, application of technologies may be limited, such as when the international community tries to react, in the midst of serious coordination and logistical difficulties, to natural disasters in impoverished countries, as was the case of Haiti in early 2010.

Two Sides of the Coin

The United Nations Platform for Space-based Information for Disaster Management and Emergency Response (UN-SPIDER) agency, a key instrument in the process of expansion that has provided incremental results acknowledged by the specialized community, highlights how reality is often quite different from what even the keenest supporters had envisioned. Here are excerpts from the UN-SPIDER report on Haiti's 2010 disaster.2 On one hand, the report says

- When the devastating earthquake of magnitude 7 struck Haiti on 12 January 2010, the UN-SPIDER SpaceAid framework was immediately activated and UN-SPIDER experts became involved in supporting the early response efforts less than 30 minutes after the earthquake hit . . . Without delay, UN-SPIDER experts began to coordinate through their well established network with providers of space-based information, including public and private satellite operators, informed them of the most pressing needs and requested tasking of their satellites . . . Precious hours were saved because of these efforts. Eventually, post-disaster imagery was made available within less than 24 hours after the event . . . In a second step, UN-SPIDER coordinated with several value adding providers to ensure that the available imagery could be used immediately to produce required services as for example maps to display accessible roads and suitable areas to set up relief facilities . . .

But the report also states

- Unfortunately, due to the disrupted infrastructure in Haiti, the huge amount of compiled data could not be downloaded by the partners on the ground via internet. Interrupted networks and low bandwidth pose a serious bottle neck, and this was also the case in Haiti.2

Certainly, responsibility in the case of developing countries lies not only in the international community. National authorities responsible for spatial information must enhance their capacity to offer assistance during disasters. In Haiti's case, the National Center for Geospatial Information collapsed, and its director, an enterprising woman who was doing a fine job, died together with a group of colleagues. In the case of the 2010 earthquake in Chile, the Military Geographic Institute provided significant help in response and recovery efforts. Moreover, upon realizing that available information was insufficient, the national government recently allocated resources to take national cartography to 1:25,000 scale.

Certainly, responsibility in the case of developing countries lies not only in the international community. National authorities responsible for spatial information must enhance their capacity to offer assistance during disasters. In Haiti's case, the National Center for Geospatial Information collapsed, and its director, an enterprising woman who was doing a fine job, died together with a group of colleagues. In the case of the 2010 earthquake in Chile, the Military Geographic Institute provided significant help in response and recovery efforts. Moreover, upon realizing that available information was insufficient, the national government recently allocated resources to take national cartography to 1:25,000 scale.

In the case of spatial data infrastructure in the Americas3, the region is progressing at its own pace, and headway has been made thanks to a set of national efforts at all levels, together with contributions from the private sector and regional projects. Nonetheless, availability of high-quality data at the supranational level is still wanting. One critical problem is the lack of effective implementation of the international standards promoted by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), not to mention those of Open Geospatial Consortium, Inc. Several programs and initiatives are making relevant contributions, such as the joint Andean Development Corporation/PAIGH program, known as GeoSUR, and the Geocentric Reference System for the Americas that successfully espouse the continental unification of the geodesic system.3

PAIGH Highlights

- Founded in 1928 and headquartered in Mexico, PAIGH assists member states with geographic and historical analyses of their territories from a continental perspective.

- It is a decentralized intergovernmental agency with 21 member states, each of which has its own national section.

- Four technical commissions are responsible for the scientific program: cartography (1941), geography (1946), history (1946), and geophysics (1969).

- The Institute is currently implementing a strategic plan entitled The PAIGH 2010–2020 Pan American Agenda, aimed at furthering regional integration through multidisciplinary actions and prioritizing natural disasters and territorial organization in a climate change scenario.

The Future of the Region's Geographic Institutes

Institutions responsible for national cartography in Latin America and the Caribbean are at a critical juncture and face the challenge of transforming their functions, skills, and human and technological resources.

Geographic institutes are no longer the sole producers of spatial information. Various public, private, local, and international institutions are equally, or better, equipped to produce fundamental spatial data and applications and make them accessible. ArcGIS Online, Google Maps, OpenStreetMap, and Bing have more and superior maps than many countries have through their institutions. The matter of who should pay for geographic information continues to be an issue. Geographic institution budgets are usually insufficient, bearing in mind the expense of the activities required to have complete spatial databases that encourage development. Guardianship, quality, integrity, and pertinence of fundamental data, as well as the tasks of coordination, certification, and verification of productive processes, access mechanisms, and data availability, are basic duties that should be assumed by geographic institutions.

Here are some key areas on which to focus to consolidate production, access, and application of the region's fundamental databases:4

- Geodesic networks (control stations, altitude and geoidal models)

- Base geographies (rectified prints, elevation models, hydrography)

- Spatial management (territorial units, geographic names, rural and urban land management)

- Infrastructure (transportation, communications, utilities)

- Soil and environment (soil coverage, geology)

To consolidate the Institute's position as the foremost Pan-American regional forum on geographic information in the region, PAIGH endorses the modernization of the geographic institutes that are responsible for national cartography in its member states, the development of spatial data infrastructures, and ISO international standards certification.

Three Types of Cartographic Institutions

There are basically three types of cartographic institutions in the region: (i) military, as is the case of Chile, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay; (ii) civilian, including some in transition, as is the case of Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela; and (iii) what we could call the Central American model, in which cartographic production is a function of the priority given to cadastre information within the framework of land management, as in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Jamaica, Nicaragua, and Panama.

PAIGH's experience invites reflection on the effectiveness observed in current capacity-building strategies, focusing more on training of human resources than on institutional and organizational development.

It would be fitting for the region to ask itself what purpose and mandate national geographic institutes should have in the twenty-first century and what the long-term plans to obtain basic strategic information in order to operate effectively are. Many variables will determine the results, and surely some are part of the decision-making process of each country, but it is clear that capacity building is at the heart of the strategy. In essence, it is a matter of education.

Training and Institutional Development Must Go Hand in Hand

PAIGH's experience compels us to reflect on the effectiveness of strategies that focus on institutional capacity building and human resource training in agencies responsible for national spatial databases. To better implement spatial information in developing countries, training and institutional development must go hand in hand. In Latin America and the Caribbean, improved results will not be attained in the short and medium term if, in addition to public- and private-sector training programs, there is no improvement in institutional management capacity. In other words, without the comprehensive strategic modernization of institutes responsible for national cartography and geography, institutional capacity building will continue to be marginal.

Technology procurement should unvaryingly be managed rationally and in such a way as to make purchases more effective. As I stated in 2003, "Technology itself does not ensure proper implementation and successful use of spatial data. Information technologies, spatial data infrastructures, and improvements in connectivity do not necessarily translate into increased access to geographic information, nor do they narrow the digital divide."5 Technological developments render formal training for data measurement and processing unnecessary. Increasingly, anybody can click a button to produce survey information and process the data in an automated system. Developments have put GIS within the reach of almost anyone. Formal training will focus on data interpretation and management. Although computers have still not replaced the benefits of personal interaction and key learning processes that are not automated, virtual academies are quickly gaining ground.6

Needed: Better Quality Spatial Data

If I had to point to one crucial aspect of training processes, I would say it is the need for better quality spatial data. It is not unusual to find digitized, nonstandardized, obsolete data generated by means of uncontrolled methods with significant margins of error, among other drawbacks. Perhaps we should begin with a clear definition of the term better quality, which would seem a simple matter but is neither evident nor accurate and, above all, is subject to a wide variety of interpretations.

To summarize, let us return to the regional vision and the meaning of the recent bicentennial celebrations. The economy is improving, and after a lost decade, many studies refer to the rise of Latin America and, on a hopeful note, to the fact that over the past 10 years, the region has experienced sustained annual growth of close to 6 percent. Nonetheless, the economies of the region have competitiveness issues or, to a great degree, are operating outside the formal economy; inequities persist. In this context, regardless of the progress achieved, I believe accessing spatial information, incorporating pertinent technologies, and designing applications to contribute to solve multiple economic and social problems, such as those related to climate change, territorial organization, and natural disasters, are essential to regional development and integration and fields in which our community has much to do.

A Note from the Author

In autumn 2010, I was asked to speak at the Latin American GIS in Education Conference held in Mexico City. There, I shared my thoughts on the connection between development, education, and spatial information technologies in Latin America and the Caribbean based on my years of experience in the field of information and development and as secretary general of PAIGH, and the above paper is the essence of my presentation, which is my personal assessment and does not necessarily reflect the views of PAIGH.

About the Author

Santiago Borrero received his master's degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and has nearly three decades of experience in information and development. Previous appointments include the chair of the Global Spatial Data Infrastructure Association and the Permanent Committee on SDI for the Americas, as well as the general director of the Agustin Codazzi Geographic Institute in Colombia (1994–2002). In Colombia, he has also been general manager of Bogot�'s Water Supply Company and the National Fund for Development Projects.

For more information, contact PAIGH secretary general Santiago Borrero (e-mail: sborrero@ipgh.org).

Footnotes

- www.undp.org/publications/index.shtml.

- Excerpts taken from "UN-SPIDER Report on Haiti."

- www.geosur.info/geosur; www.sirgas.org.

- Clarke, Derek. Determining the Fundamental Geo-Spatial Datasets for Africa, 2007. www.agrin.org/feature.php?id=22

- Borrero, Santiago, UNSIS, CERN, 2003.

- Williamson, Enemark, Wallace, Rajabifard. Land Administration for Sustainable Development, Esri Press, 2010.