ArcNews Online

Fall 2010

[an error occurred while processing this directive]Environmental Advocate Creates Path to More Informed and Effective Conservation Efforts

Every once in a while, you meet individuals who impress you with their ability to build a rewarding life and innovative career based on uncompromised ideals. Steve Beckwitt is one of them and is a GIS hero. His passion for conservation led him to become a pioneer in the use of GIS to assess and protect our natural resources.

Every once in a while, you meet individuals who impress you with their ability to build a rewarding life and innovative career based on uncompromised ideals. Steve Beckwitt is one of them and is a GIS hero. His passion for conservation led him to become a pioneer in the use of GIS to assess and protect our natural resources.

He carries out his work from his home on an organic farm in the Sierra Nevada foothills, which—as you'll soon find out—is where his family's remarkable conservation story began in the 1980s. What started as a heartfelt effort initiated by his two sons to protect old-growth forests turned into a career supporting scientists, organizations, and governments around the globe in using GIS to better manage our land and water.

Building an Environmental Consciousness

Steve Beckwitt, above center, in old Lhasa, Tibet, near the Jokhang Temple. Beckwitt was in the country to work on a GIS project to establish citizen-managed protected areas. Also pictured is a Tibetan prince from Chamdo in eastern Tibet (left) and a Tibetan Buddhist monk (right).

Beckwitt developed an awareness of the importance of conservation at a young age. Particularly compelling was the time he spent exploring the natural environment in the Desert Hot Springs area of California with an older cousin, Dorothy Green, who went on to become a water conservation advocate and founded Heal the Bay in Santa Monica, California.

"We kind of coevolved a conservation ethic and understanding together just by discussing and reading about environmental issues," says Beckwitt.

Beckwitt's time as a student at the University of California, Berkeley, in the 1960s was another important catalyst in shaping his conservation career. Among other "green" endeavors, he contributed to the creation of an environmentalist take on the Declaration of Independence called the "Unanimous Declaration of Interdependence," which influenced Greenpeace's famous 1976 "Declaration of Interdependence."

Just short of completing a Ph.D. in biophysics, he left Berkeley for the wilderness of the Sierra Nevada. In the 1980s, his two young sons expressed an interest in botany, inspiring the launch of a family nursery business. They propagated several hundred species of unusual and difficult-to-grow native plants, as well as over a thousand other Mediterranean plant species, which they sold to many of California's botanical gardens.

Conservation Activism: A Family Affair

In the process of gathering seeds and cuttings for their nursery, the Beckwitts noticed alterations in the landscape. At the time, significant areas of the Sierra Nevada Mountains were being clear-cut, resulting in the degradation of the ecosystem.

Beckwitt and his sons, who were teenagers at the time, founded the nonprofit Sierra Biodiversity Institute to submit scientifically based appeals to protect old-growth forests in the Sierra Nevada Mountains under the provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

"We did our own fieldwork," says Beckwitt. "We evaluated the landscape and tried to discover what potential ecological impacts were not addressed in the original NEPA documents and called them out with photographs."

This work was done before the U.S. Forest Service or the Beckwitts were using GIS technology, but the appeals did include Forest Service maps overlaid with data on environmental aspects that had not yet been considered in policy making.

"My sons really were the lead," he adds. "I helped them when they needed help, but most of the work they did themselves."

They won 23 of the 24 appeals they submitted, and most of them were reviewed by the Forest Service at the national level. The Beckwitts' technical appeals, along with the work of many other concerned citizens, prompted the Forest Service to reverse forestry policy decisions and readdress environmental issues raised in the appeals.

What GIS Means for Conservation

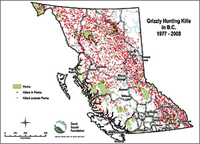

This image, depicting grizzly bear killings in British Columbia, was produced for the media as part of a series of GIS analyses on endangered species, which Beckwitt performed for the Suzuki Foundation of Canada.

In 1989, Beckwitt was asked to write an article on ecological restoration for the Whole Earth Review, an alternative culture magazine of that time. He had read about GIS technology and was interested in its potential uses in restoration planning. He researched and wrote about this emerging technology and quickly began to use GIS in his conservation work.

The Sierra Biodiversity Institute incorporated the data it gathered in the field with quad maps from the U.S. Geological Survey, which the Forest Service had just captured as cartographic feature files (CFFs). Using ARC Macro Language, the group translated CFF data for the entire Sierra Nevada into ArcInfo format.

"We used GIS to prepare a full-fledged dataset for the Sierra Nevada, then captured a lot of timber cutting history and made what were among the first presentations using GIS to Senate and congressional staff," says Beckwitt. "It was all about educating the public and our legislators about the landscape impacts of the forest practices of the time."

In the 1990s, Beckwitt began focusing on professional GIS consulting work, primarily in support of academic scientific research projects. He contributed his expertise to an assessment of the Pacific Northwest's Inland Empire, published by the Wildlife Society, which eventually led to a major Forest Service study. He trained graduate students at the University of California, Davis, to use GIS for the Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project, a regional landscape assessment requested by Congress in 1992. Later, among many other consulting projects, he provided fire impact modeling for Grand Canyon National Park's Environmental Impact Statement.

"Once GIS became available, it was impossible to do a thorough assessment without it because of the power of the tools and the ability to explore relationships between different themes," says Beckwitt. "GIS is fundamental for inventorying the various facets of our environment and for developing indicators to monitor and assess environmental change over time. It helps guide public policy—and personal policy, too."

By this point, Beckwitt was also consulting internationally. Under a U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) grant, he and one of his sons traveled through Russia to evaluate how GIS could be applied toward conservation efforts in protected areas that were struggling after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Shortly thereafter, he met a representative from the Wildlife Institute of India who was preparing a presentation on the Narmada Dam for the World Bank. Beckwitt assisted with the GIS analysis portion of the presentation, which communicated the potential impact of the dam and had a powerful effect on policy. The Wildlife Institute of India then asked him to become a United Nations consultant. In that capacity, he trained scientists to integrate GIS into their wildlife research and helped establish a database of protected areas, including tiger and elephant habitats.

In 2006 and 2007, Beckwitt worked with a team of scientists to establish citizen-managed protected areas in the Four Great Rivers region of eastern Tibet. In 2008, Tibetan political turmoil limited access to the area and halted the project. "We'd love to go back and continue," he says.

Sharing Technology to Help Preserve Natural Resources

For the past 20 years, Beckwitt has helped others pursue their conservation efforts by advising Esri on its grants of GIS technology to deserving organizations. He helps ascertain each organization's goals, accomplishments, resilience, and technical capacity and determines which products best meet their needs. He continues to support grantees by evaluating maintenance grant requests to keep their GIS technology up-to-date. In addition, since 1996, he has consulted for the U.S. Forest Service and other government agencies on their conservation-related contracts with Esri. He also currently serves as the senior GIS consultant to the State of California's Sierra Nevada Conservancy.

Beckwitt cites several exceptional examples of large organizations leveraging GIS technology to advance conservation efforts, such as the Nature Conservancy and the Wilderness Society. Those that stand out the most to him, however, are small, grassroots organizations, such as the Pacific Biodiversity Institute, that use GIS to create maps and models to analyze vegetation and habitat suitability.

"I'm most proud of having been involved in helping thousands of organizations get GIS projects up and running and providing technical support when needed," notes Beckwitt. "If I were to look back at my life in terms of having an impact on the world, that's probably it. It was a small impact, but it was wide ranging, and I'm glad I did it."

More Information

For more information, contact Steve Beckwitt (e-mail ecp@esri.com and put @steve anywhere in the subject line).