ArcNews Online

Fall 2010

[an error occurred while processing this directive]Conservation Group Seeks to Save Rare Ethiopian Wolves

Rabies Threatens Endangered Species in Africa

By Christopher H. Gordon, Graham Hemson, and Anne-Marie E. Stewart, Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme

Highlights

- GIS mapped where vaccinations were concentrated from year to year and where to target vaccinations in the future.

- ArcGIS maps convinced Ethiopian authorities to allow vaccinations.

- The locations of carcasses were mapped along with previous data on pack locations and viable habitats.

Ethiopian wolves, the rarest canids in the world, face many threats to their survival. One of the most serious comes from rabies, transmitted to the animals from domestic dogs.

To protect the wolves, the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme (EWCP) (www.ethiopianwolf.org), with help from other organizations, operates a rabies vaccination program that uses GIS technology to target the best locations to vaccinate the dogs and wolves that will prevent the spread of the virus.

The Danger the Wolves Face

Fewer than 450 Ethiopian wolves still roam the mountainous regions of Ethiopia, Africa. They live at altitudes of more than 9,800 feet and are only found in seven isolated populations. The largest comprises 250 wolves that make their home in the protected area of the Bale Mountains National Park (BMNP) in south central Ethiopia.

EWCP was founded in 1995 to promote sustainable solutions for protecting the Ethiopian wolf. The organization mainly focuses its efforts in and around BMNP.

EWCP takes a three-pronged approach to saving the wolves: Educating people about the importance of protecting the wolves, monitoring the wolf populations, and vaccinating the wolves and local dogs against diseases.

The Ethiopian highlands, where the wolves reside, have become some of the most densely populated agricultural areas within Africa. With human development surrounding and encroaching on the animals' habitat, the wolves are confined to small areas and isolated from other wolf populations.

The majority of people living here are pastoralists, and their livestock overgraze and trample the natural Afro-alpine habitat. With the climate warming, the cultivation of crops at high altitudes is becoming more viable and results in the loss of indigenous plant species. This leads to the destruction of habitat for rodents, which are the wolves' main prey.

While the Ethiopian wolf is threatened by habitat loss, and thus prey reduction, persecution, and hybridization, diseases transmitted from the local domestic dog population remain the primary threat to the species. There were rabies outbreaks in Ethiopian wolves in BMNP in 1991–92 and again in 2003–04. This disease is fatal, and in past known cases, it has killed at least 70 percent of wolves in the core infection area. This is obviously a significant threat to an already critically endangered species.

Vaccination Program Gets Under Way

In 1996, EWCP launched a domestic dog vaccination program, aiming to vaccinate 70 percent of the 20,000 dogs living in and around the national park. Theoretically, such vaccinations would curtail the disease and stop it from spreading to the wolves. However, dogs have a tough life and a short lifespan in Ethiopia, with many vaccinated dogs dying young and puppies constantly being born that need to be inoculated. Furthermore, during the dry season, herders and their livestock and dogs travel into wolf range from many miles away to take advantage of the grazing still available within the park. This increased contact with the Ethiopian wolves raises the risk of rabies spreading to the wolves.

Currently, EWCP can only afford to vaccinate 7,000 dogs per year (at a cost of $6 per dog). All these factors combine to make it extremely difficult to vaccinate 70 percent of the local domestic dog population and ensure the wolves will be protected.

Dr. Jorgelina Marino, EWCP's ecologist, first began implementing ArcGIS software in 2005 with support from the Society for Conservation GIS (SCGIS). ArcGIS was used to collate data collected by the organization's wolf monitoring team on wolf distribution, individual pack territories, and habitat availability. Using GIS, EWCP mapped where vaccinations were concentrated from year to year and more efficiently planned where to target vaccinations in the future.

A wolf released after a vaccination (photo copyright � Anne-Marie E. Stewart).

Understanding a Rabies Outbreak

During a recent rabies outbreak among Ethiopian wolves, ArcGIS software helped EWCP stop the disease from spreading.

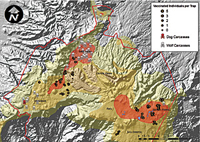

Most wolves in BMNP are split into three linked subpopulations: Sanetti Plateau, Morebawa, and the Web Valley. In late August 2008, EWCP researchers in the Web Valley found a dead Ethiopian wolf. The monitoring team regularly discovered more carcasses from early October 2008 onward, with laboratory testing confirming seven rabies cases. As each case was discovered, it was added to a rapidly growing GIS layer of the area, helping EWCP better understand the likely origin of the outbreak and which direction it was spreading through the population. The rabies had been carried into the wolf range by a rabid dog, which must have bitten a wolf. Wolves are social pack animals (once one has rabies, the disease spreads quite rapidly).

Thirty-nine carcasses were recovered from the Web Valley between August 28, 2008, and January 15, 2009. Because EWCP researchers are so familiar with the wolf population there, they knew 13 more wolves were missing from the area.

Due in part to the information gained from mapping the outbreak, EWCP received permission from Ethiopian conservation authorities to vaccinate 50 wolves against rabies. Permission for vaccinating wolves is only granted by the authorities once a rabies outbreak has occurred.

The intervention began on October 20, 2008. The objectives were to contain the rabies virus within the Web Valley and reduce the probability of BMNP wolves becoming extinct by protecting wolf packs in other key adjacent subpopulations.

Effective planning for such an endeavor is critical, and ArcGIS Desktop ArcView excelled in this task. The locations of discovered carcasses were mapped, along with previous data on pack locations and viable habitats.

Based on the maps and EWCP's understanding of the two previous rabies epidemics, the disease's potential spread was estimated. Decisions about where to set the live traps for the wolves were also made before mobilizing the vaccination team. Since restrictions exist on the number of wolves that can be vaccinated, it was crucial to ensure that every vaccination was utilized to maximum effect.

As Morebawa was the most immediately threatened subpopulation, trapping the wolves for vaccination was focused on the Web Valley, East Morebawa, and the Web Isthmus (a small corridor) between these two populations.

During more than 1,200 hours of trapping, 50 wolves were vaccinated from 11 packs. Vaccination efforts were based on population viability modeling outcomes showing that, if 40 percent of the wolves in each pack were vaccinated, the probability of that pack's survival would increase from 54 percent to 90 percent.

But despite wolf vaccinations conducted in October, rabies was spreading swiftly through the domestic dog population around the national park. The EWCP team began to find wolf carcasses from West Morebawa in early May 2009. In total, 11 carcasses were found, while the monitors only identified 32 live wolves in a population that should have numbered closer to 90. Samples were collected from one wolf, and it tested positive for rabies.

Authorities again granted EWCP permission to vaccinate 50 wolves. By the time the outbreak was discovered, however, it was considered too far advanced to protect the remaining wolves from the West Morebawa area. Fortunately, 8 of the 32 remaining wolves had been vaccinated against rabies during the 2003 epidemic. EWCP focused the second intervention effort on the third major subpopulation, the wolves on the Sanetti Plateau, and vaccinated 48 wolves from nine packs in fewer than 700 hours of trapping. During the second trapping effort, two more carcasses were discovered on the Sanetti Plateau. Both were juveniles, found dead at a time when mortality would be naturally high in individuals of that age due to their recent independence and inexperience in finding food. They tested negative for rabies.

Benefits of Long-Term Monitoring

The swift response to outbreaks such as these could not be possible without EWCP's long-term population monitoring program. Strategic decisions were made based on in-depth demographic knowledge about the carcasses discovered and wolves that were missing. This knowledge was also integral for implementing the rabies vaccination program and postintervention monitoring. Combined with new technologies such as GIS, EWCP launched rapid and effective intervention procedures. Reactive intervention campaigns are costly, both financially and in terms of potential loss of population size and viability. Careful planning helps reduce the costs somewhat while increasing the effectiveness of any action taken.

The constant threat of rabies and the past history of two previous known outbreaks combined with this current epidemic suggest that this problem is not solved yet. Despite the early detection, a significant number of wolves in BMNP still died.

An estimated 67 percent of wolves from six unvaccinated packs in Web Valley and 73 percent of wolves in West Morebawa were lost. In all, the 50 carcasses and 66 missing wolves represent approximately 36 percent of BMNP's wolf population and possibly more than 25 percent of the global population, (a worrisome and real threat to a wonderful species).

About the Authors

Christopher H. Gordon, Graham Hemson, and Anne-Marie E. Stewart are with the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme, Robe, Bale, Ethiopia, of the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom.

More Information

For more information, contact Dr. Jorgelina Marino, EWCP ecologist (e-mail: jorgelina.marino@zoo.ox.ac.uk), or the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme, Robe, Bale, Ethiopia, at info@ethiopianwolf.org. Acknowledgments are online.