Drone2Map for ArcGIS Helps Re-create Historic Native American Site

From AD 900 to 1200, a Native American population inhabited about 20 acres in Aztalan, Wisconsin, which lies 40 miles east of the current state capital of Madison. According to archaeologists who have studied the site, the village was well-planned with agriculture that included beans, corn, and squash and village life that involved organized ceremonies.

Most of the village was encompassed by a wooden barrier, and there was a sizable plaza in the middle, demarcated by two platform mounds and a natural knoll. It is believed that at least some of the inhabitants of Aztalan were part of a bigger, more complex society—the Mississippians—that can be traced back to Illinois, near what is now St. Louis, Missouri. Not much else is known about the 500 or so people who inhabited Aztalan and their lifestyle, though the site, which is now located in Aztalan State Park, is one of Wisconsin’s most important archaeological locations.

To dig into deeper layers of this Native American community’s existence, archaeologists need new ways to document the excavation site. In the past, the mounds—which may have served some religious purposes—were reconstructed, and archaeological digs take place on occasion to unearth clues as to how and why the site was constructed. But to build a comprehensive map of the place and get a better idea of how the population might have lived, it was imperative to get aerial views of Aztalan.

For years, archaeologists have used regular photography and hand drawings to document full archaeological sites. To get a bird’s-eye view, they have typically relied on cherry picker cranes and specially erected scaffolding. But with high-precision drones equipped with high-resolution cameras, getting overhead views of archaeological sites has become much easier. One aerial photograph rarely covers an entire site, however, so drone-supplied aerial photos need to be stitched together.

Drone2Map for ArcGIS offered a great solution to this challenge. Working directly with ArcGIS, the app can quickly process a series of aerial photographs into orthomosaics and 3D textured meshes, which can then be used to create a realistic reconstruction of portions of the site as they looked originally. This was my goal for Aztalan.

Capturing Aerial Images of the Site

For the project, I used a DJI Phantom 3 Advanced drone, a reliable unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that supports EXIF data natively. Having this metadata—which includes the location, altitude, and camera settings for each photo—is key to correctly positioning the images.

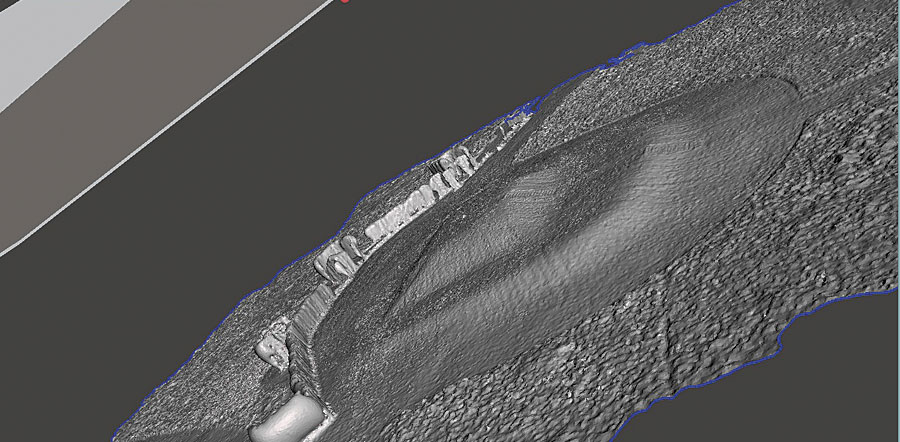

With the remote control connected to an iPad, I flew the drone in a grid pattern over the main mound at Aztalan and took nearly 40 aerial photographs from an altitude of 100 feet (30 meters) above the mound. Aiming the drone straight down to produce nadir images worked best, since it captured visual data for all sides of the moderately slanted mound while excluding data from the background.

After the flight, I uploaded the photos to ArcGIS Online, where Drone2Map read the EXIF data and started the process of building the orthomosaic and 3D mesh. Using key points in the images, such as poles or corners of steps on the stairs, Drone2Map automatically deciphered how the photographs overlapped and linked them together. In about 15 minutes, Drone2Map generated an imagery basemap (from the orthomosaic) and assembled a high-quality 3D diagram of the main mound.

Re-creating Aztalan in 3D

With these outputs from Drone2Map, I then imported the OBJ file for the 3D mesh into Daz Studio, a software from Daz3D that allows users to create static scenes of people and their surroundings. Using visual clues based on findings from other historians and archaeologists—such as drawings from Aztalan: Mysteries of an Ancient Indian Town, by Robert Birmingham and Lynne Goldstein, and artifacts from local museum exhibits about the site—I generated a 3D rendering of what Aztalan might have looked like 800 years ago.

For archaeologists, getting a complete 3D view of a site can serve several purposes, including representing an area as it exists today or virtually re-creating an archaeological site to envisage what it might have looked like in the past. For instance, in places where archaeologists find the foundation of a building, they can use drone-generated aerial images and 3D modeling software, such as Esri CityEngine, to reconstruct the columns and walls of a building so they can conceptualize what it used to look like and how the building factored in to the rest of the environment. Or in Aztalan’s case, just having the mound represented in 3D allows archaeologists and historians to see what it might have been used for and how the wooden barrier could have factored into everyday life.

“We can better understand the lives of these ancient people by viewing them in their actual environment, as re-created through 3D renderings,” said Karen Kitover, a docent at the Loyola University Museum of Art in Chicago.

And using drones—along with Drone2Map—makes producing these 3D renderings much easier. As IT specialist and computer engineer Roland Kunz (who helped me configure the drone) pointed out, “The virtual reconstruction of Aztalan shows us…what can be achieved with drones [in archaeology] going forward.”

About the Author

Andreas Forrer, PhD, studied Aztalan as part of his thesis project for the Newburgh Theological Seminary and College of the Bible in Indiana, where he recently received a second PhD in archaeology. For more information about this project, email Forrer.